Teaching Histories of Graffiti

“Wait, what!? How do you even teach this kind of history?” “What kind of texts do you use in class?” “Isn’t that too recent to be history?” These are the kinds of questions that I sometimes hear when I tell folks that I am teaching a course on the history of graffiti in the Americas. They are usually well meaning and curious, rather than dismissive or incredulous. Thus, every time I hear one of these or similar questions, I become more and more aware that the curiosity I am hearing isn’t based so much around whether or not graffiti merits attention as a worthwhile topic of study. This issue thankfully doesn’t really seem to be a question among my colleagues. Instead, the curiosity seems to stem from a query of whether or not history as a discipline can offer us anything about the study of graffiti.

To a certain degree, I understand the curious disbelief. Many people who hear the word “graffiti” immediately think of the 1970s and 80s in New York City and that is about as far back as their historical conception of the word can go. On the one hand, this way of thinking about graffiti attests to the gargantuan impact that New York “writers,” “bombers,” “taggers,” and “piecers” have had on the shape and the imagination of 20th century graffiti. But the history of graffiti is in fact much longer than this, and the explosion of subway art that came out of New York after 1970 was in many ways a transformation and a continuation of a centuries long practice of humans writing and painting on public walls and surfaces.

Let me be clear. In saying that graffiti of the 1970s comes out of a centuries long set of practices I am not saying that there was nothing new about modern graffiti subculture. What I am saying is that in the technical sense of the term, graffito–or to write or scratch figures into a surface other than paper–has come in many forms and methods of expression prior to its current iteration. Hence it may be worth considering the ways that some of these antecedent methods have parallels with or have informed contemporary graffiti.

Where does one begin then? What are the antecedents and the legacies of writing on the wall that the so-called modern graffiti subculture of the 1970s and 80s inherited? Possible answers to these questions may not be found exclusively in U.S. history, but perhaps in the entangled trajectories of late 19th and early 20th century Latin American and U.S. history.

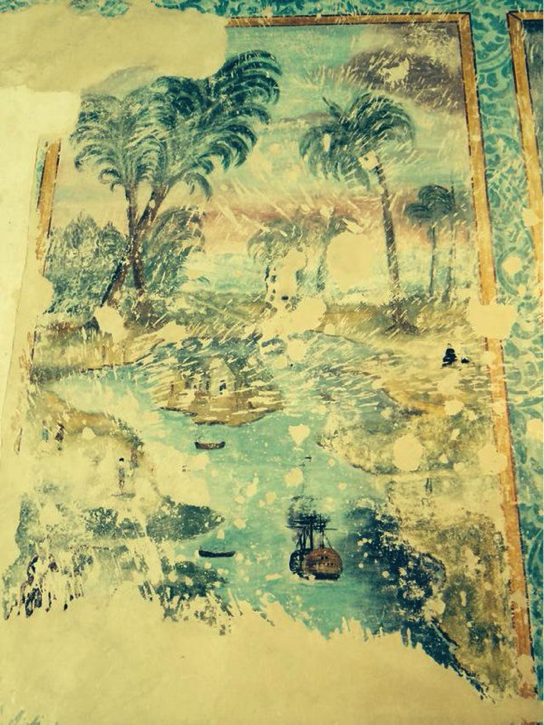

Cuban history, for example, offers at least one antecedent to what we know as graffiti. Long before there was a culture of writing on subway cars in New York, there was a culture of wall painting in Havana. Scenes of African descended men and women in 19th century parlor attire, paintings of animals in landscapes, and inscriptions associated with particular Afro-Cuban brotherhoods once covered the walls both interior and exterior of private homes and public buildings. In fact, such painted scenes were ubiquitous enough in the 1850s and 60s to prompt elite whites to lament out loud that all of the arts were in the hands of the people of color. While this had not seemingly been an issue in decades before, the move to push people of color out of positions of artistic prominence in the second half of the 19th century can only be read as part of the colonial state’s reaction to the cycle of slave rebellions that took place in Cuba between 1841 and 1844. 1

Thus over the course of two decades this kind of work and the artists who were associated with it were phased out of work and out of circulation. It was thus most certainly an episode where Afro-Cuban modernity was disavowed and disallowed. It was also clearly about what kinds of artists and races should have access to and use of space.

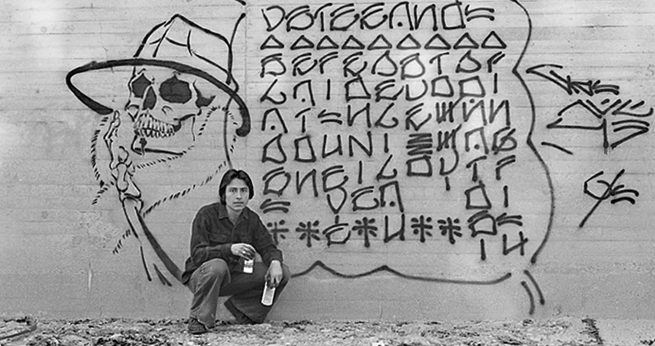

The works of Mexican muralists from the era of the Mexican Revolution were also undoubtedly major antecedents to contemporary wall writing. It is not just that it was art that was executed on walls that can account for the importance that this mural work had in shaping the late 20th century trajectory of graffiti. It is rather the fact that young Mexican Americans who wrote and painted graffiti from the 1930s through the 1960s and 70s in LA were undoubtedly influenced by this revolutionary art.

While most popular histories of graffiti do acknowledge the importance of Mexican-American graffiti from the 1930s to the overall history of wall writing, more often than not these histories still separate this moment in Mexican American and Los Angeles history from the history of black and Latino youths who wrote and painted train cars in the 1970s in New York City. The argument is usually one that sees Mexican-American contributions to graffiti to be synonymous with gang culture (i.e. Graffiti as marking territory), while the New York variant introduced style and artistic flair into what was otherwise little more then gang signs and names written in old English letters. 2 Yet what is often overlooked in these cursory divisions between gang graffiti and “artistic” graffiti is the curious development of a particular slogan that was central to graffiti writers from gangs in 1930s and 40s LA: “con safos.”

Not precisely translatable in English, the phrase “con safos,” often written as “C/S” for short, can roughly be understood as equivalent to saying “the same to you.” It was often included at the edge of or around the borders of a graffiti tag or piece as a way of safeguarding against the tag or name from being crossed out. In short he or she who crossed out the con safos would, by the rules of the slogan, be crossing themselves out. While this may have been attached to gangs who tagged their respective blocks and spaces, it was also picked up by kids and stylized. Thus at a certain point, “con safos” both maintained its original function and became an artistic endeavor in its own right, with young Mexican-Americans experimenting with letters, styles, angles, and framing of the words just like style masters of New York City graffiti would also turn to doing in the 70s and 80s. 3

From wall painting in Cuba to muralists in Mexico to Mexican-American youths and the development of “con safos”: this is the historical trajectory I am teaching through this semester, and these are what I believe to be sorely under acknowledged elements in the narratives we have developed about graffiti’s development in the twentieth century. Whether one believes I’m ultimately right or wrong in highlighting these connections specifically, the fact remains that there is no reason to think about or teach a history of graffiti as a history of the present. Antecedents to what we already know from our exposure to graffiti are there, we may just have to look beyond the borders of the U.S and as far back as the late nineteenth century to see them.

- On wall painting, see Sibylle Fischer, Modernity Disavowed: Haiti and the Cultures of Slavery in the Age of Revolution (Durham: Duke University Press); On 1841-1844 rebellion, see Aisha Finch, Rethinking Slave Rebellion in Colonial Cuba: La Escalera and the Insurgencies of 1841-1844 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina press, 2015) ↩

- For example of this history, see Steve Grody, Graffiti L.A.: Street Styles and Art (Harry N. Abrams, 2007), 11-12. ↩

- Sylvia Ann Grider, “Con Safos: Mexican-Americans, Names and Graffiti,” The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 88, No. 348, 1975), 132-142. ↩