The Radical Democracy of the Movement for Black Lives

“Black Lives Matter has cast a strobe-light on contemporary myths of racial progress, arguing correctly that the criminal justice system represents a gateway to a panoramic system of racial and class and gender and sexuality oppression.”

The Black Lives Matter policy agenda represents one of the most important agenda setting documents collectively produced by black activists in a generation. The proposals, authored by over fifty different civil rights organizations, offers a panoramic narrative, diagnosis, and political alternatives to the intricacies of structural racism, state-sanctioned violence, and the institutional exploitation of black bodies across the nation.

“A Vision For Black Lives” builds on, expands, and goes beyond policy agendas promoted by a range of civil rights and Black Power era groups, including the Black Panthers, Nation of Islam, NAACP, SNCC (the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee), CORE, Malcolm X’s Organization of Afro-American Unity, and Martin Luther King Jr’s SCLC. In its poignant urging of the United States to “end the war on black people,” the document is reminiscent of the “Gary Agenda,” the historic 1972 document that emanated from the National Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana.

That meeting of over 8,000 black delegates from across black America’s political and ideological spectrum proved to be a watershed event, albeit one that was hamstrung by an inability to translate grassroots insurgency into tangible political power, accountability, and resources. Gary, like the Black Power Conferences from the late 1960s and the African Liberation Day and Sixth Pan-African Congress of the 1970s, sought to modernize the black convention movements that could be traced back to the Reconstruction era, where black activists organized for political power in slavery’s aftermath.

By the early 20th century efforts like the “Niagara Movement” faltered due to a lack of resources and political infighting. For a time, Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association cast a shadow large enough to encompass the complexity of black life, uniting economic strivers with revolutionary activists in developing a black agenda broad enough to attract millions of black people across several continents.

Garvey’s decline fractured aspects of black political life, but not dreams for a cohesive vision, plan, and strategy for black liberation, a cause taken up during the Depression and Second World War by a variety of groups including the Southern Negro Youth Congress, National Negro Labor Congress, The Nation of Islam, the Civil Rights Congress, and the Council of African Affairs. The NAACP’s membership reached almost a half-million by 1946, the closest it would ever come to mass membership in scale. Black political leaders pushed an agenda to the left of the New Deal creating space for the global popularity of Paul Robeson, the political resurrection of W.E.B. Du Bois, and the insider status of Mary McLeod Bethune and Ralph Bunche.

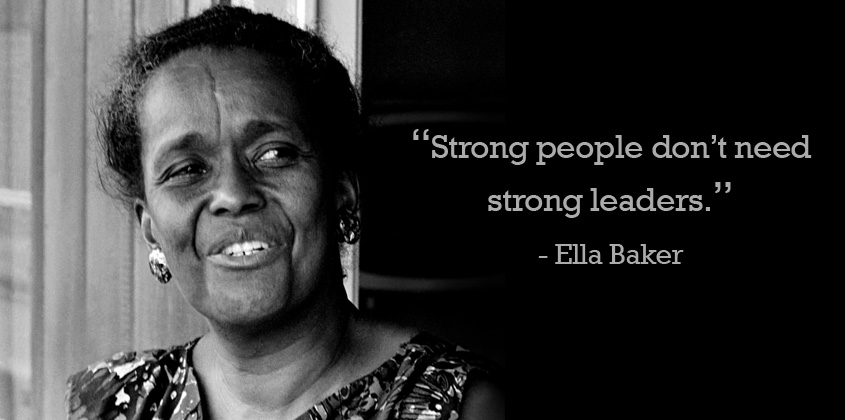

Organizers like Ella Baker in New York City and Septima Clarke in South Carolina, worked the lower frequencies of black life, working at the margins of the black quotidian: the ordinary black folk from New York to South Carolina whose dreams remained disarmingly pragmatic ones focused preserving hope and dignity.

The Black Lives Matter Movement is rooted in this wider Black Freedom Struggle, one whose two dominant branches are reflected in the Civil Rights and Black Power era. BLM activists’ successful adoption of non-violence is rooted in the civil rights era even as their unapologetic focus on structural racism, community control, and political self-determination reflects the Black Power era’s radical politics. Surprisingly, so does the movement’s focus on intersectionality. Popularly remembered as deeply masculinist, unapologetically sexist, and homophobic, the Black Power era proved to be more complicated than such simple generalizations indicate. Despite the movement’s many political and ideological blinders, black women, queer activists, and others on the margins of African American life consciously shaped an expansive Black Power politics.

The Third World Women’s Alliance articulated a vision of radical black feminism, socialism, and Black Power militancy that made it a visionary example of cutting edge social justice movements. The Combahee River Collective gave voice to radical black lesbian feminists whose politics went to the far left of the more mainstream National Black Feminist Organization. In many ways both of these organizations reflected the black radical feminist politics revealed in Toni Cade Bambara’s groundbreaking 1970 anthology, The Black Woman, an intellectual and political intervention that ushered in Black Women’s Studies and helped give attention to the works of Audre Lorde, Barbara Smith, Gloria Hull, and many others.

BLM activists have taken some of the best aspects of these two generations of the Black Radical Tradition and linked it with more recent efforts to promote reparations (especially by grassroots a organization like N’COBRA, although reparations go back to the formerly enslaved activist Callie House as the historian Mary Frances Berry teaches us); divestment from domestic and global racial exploitation which Jesse Jackson, especially in 1984, promoted as a hallmark of his presidential campaign; the pursuit of independent black political power that had been advocated in the post Gary era by a series of organizations including the National Black United Front, the National Black Independent Political Party, and the Black Radical Congress; the movement for economic justice that has been promoted by a spectrum of grassroots labor, community, church, and secular activists, including black nationalists in communities such as St. Petersburg, Florida, who famously booed candidate Obama in 2008 by chanting and holding signs, “What About the Black Community Obama?”

Black Lives Matter has cast a strobe-light on contemporary myths of racial progress, arguing correctly that the criminal justice system represents a gateway to a panoramic system of racial and class and gender and sexuality oppression. This intervention, while important, is incomplete without an acknowledgment of the way in which the rise of mass incarceration is connected to systems of racial segregation, voting rights denial, state-sanctioned violence and exploitation of black bodies, all while criminalizing and decimating the very communities that remain largely under assault even in the Age of Obama.

The Age of Ferguson, Baltimore, Milwaukee, Black Lives Matter has shattered conventional civil rights narratives, ones that begin with Rosa Parks, continue with King’s Dream, and sought to end with Barack Obama’s election. This version of history as a bedtime story, complete with heroic individual blacks, stalwart white allies, and the thanks of a grateful nation has only one glaring problem.

It’s a lie.

The Civil Rights era heroic period experienced pervasive anti-black violence that only increased during the Black Power era and its aftermath. What is now universally acknowledged as a moral and political good—complete with a multiracial cast of characters—was demonized in word and deed by the larger society, a denigration that became inscribed in a series of intricate anti-black legal, legislative, and policy challenges that have utterly decimated some of the gains of the era, especially for the black poor.

“A Movement For Black Lives” is essential precisely because it helps to expose what is at the root of our national amnesia regarding slavery and anti-black racism-white supremacy and its relationship to conceptions of citizenship, the rule of law, democracy, and justice. In its passionate repudiation of the political status quo and elevating the lives of the black community’s most vulnerable residents—the poor, young, elderly, trans, LGBT, mentally ill, incarcerated, ex-offenders—the BLM has produced a watershed document that once again illustrates why the black freedom struggle has always been on the cutting edge of movements for radical democracy: we have no choice.

Peniel Joseph is the Barbara Jordan Chair in Ethics and Political Values and director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the LBJ School of Public Affairs and Professor of History at The University of Texas. He is the award-winning author of several books, including Waiting ‘Til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America, Dark Days, Bright Nights: From Black Power to Barack Obama, and Stokely: A Life. Follow him on Twitter @PenielJoseph.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.