An Open Letter to White Liberal Feminists

Dear White Liberal Feminists,

After Donald J. Trump’s election to the highest and most powerful political office of the United States last week, many of you have approached me, and my black brothers and sisters especially, with tearful eyes and somber faces. In person, in private, in public, and in the digital sphere, you have bemoaned the state of this world and our political landscape. You have lamented the deep-seated divisiveness of this country. You have wept, you have hugged, and you have gingerly asked, “how are you?”

And yet, your actions and inquiries are especially loaded, as much for their selfishness as their disingenuous nature. Your hugs and tears are of the self-soothing kind. Your inquiries seldom derive from a true desire to learn about how I, as an African American woman, really feel. Rather, your queries posit, in the most passive aggressive way, “Aren’t you as upset about the election results as I am?” “Aren’t you embarrassed to be who you are?” “Aren’t you sorrowful that your parents, and your in-laws, and your siblings, and your friends in towns and cities and states voted for Donald Trump?” “Aren’t you ashamed to know that the women of your race also voted against so very many of theirs and others’ interests?” “Aren’t you devastated that the first female candidate—our candidate—to earn the Presidential nomination for a major party did not win and allow us to make history for women?”

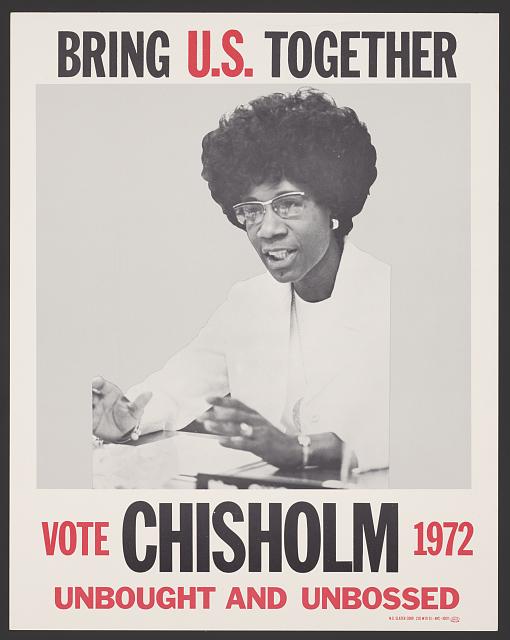

I am none of those things and I share none of these sentiments, in large part because these queries are not my narrative. I am ultimately not surprised by the most recent outcome of the election (and I am familiar enough with history to recall the inimitable, Shirley Chisholm, the queen of the “unbossed and unbought” perspective). I find your overall shock at the role white women voters played in the election curious for its naïveté and annoying for its obtuseness.

If there is a sentiment we share, it is disappointment. I am disappointed that it has taken you this long to actually get what black women—and namely black feminists and womanists—have been trying to help you see and feel for a very long time. We now, for example, share fear. But my fear has been tempered by the legacy of slavery and anti-black racism in this country. You now worry for your children, your family, and your brothers and sisters. I have been worrying for mine.

And if I am being honest (and we can be honest, right?), I am also a bit delighted. I am delighted that you have received the potential awakening of a lifetime, and that now you might actually get what so many of us have been describing all along. Welcome to that deep perpetual angst. Embrace it, and allow it to motivate you to a deeper form of action.

I am also thrilled about how this moment might signal an end to the dangerous, disingenuous version of feminism that so many (though not all) of you embrace, and which promotes white women’s success over and against anyone else. It is the brand and tenor of white feminism that allows for a recapitulation of white male patriarchy (à la white women merely behaving as white men in drag and putting on the farce of gender equity). It has long been your trope and now it is your bane.

But what will you do with this newfound dismay? How will you interrogate and sustain your recent enlightened perspective about how white women remain complicit in the oppressions of so many non-white folks, and even themselves? Given your responses this week and the last, I am already seeing a kind of writing on the wall—that of denial. So few of you have commented on the implications of large numbers of white women voting against Hillary Clinton. So few self-proclaimed white liberal feminists interrogate racism, imperialism, capitalism, and sexism because they benefit from it and are too busy being protected by it.

What then, is the efficacy of this particular brand of white feminism in our current moment? If this most recent presidential election has revealed nothing else, it has shown that this specific ilk of white feminism must die.

In this moment, if I have any regret, it is that you are trying to force me to be complicit in your self-denial, and that you expect me to do yet another kind of labor. You look, of all places, to me to help you deal with your feelings. Rather than holding up your weeping, weak selves, I have a few questions for you to consider: Who will you be in this hour? What will you do to enact change and with whom will you partner to do it?

By all means, use whatever mechanism you require to move through the stages of grief as you bury your false idol of faux feminist solidarity. You must now do the intensive work to heal your troubled soul. And after you have come to terms with your own guilt, embarrassment, and pain, I encourage you to run with your newfound perspective. There is a terrifyingly beautiful lineage of black resilience—seasoned by black suffering—that you might turn to for hope.

I especially urge you to read up. A host of syllabi and materials posted here on AAIHS (including #Lemonade: A Black Feminist Resource List) can help you, as can this powerful reminder from The Combahee River Collective’s “A Black Feminist Statement:”

The most general statement of our politics at the present time would be that we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression and see as our particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking. The synthesis of these oppressions creates the conditions of our lives.

For more recent commentary, Kali Holloway’s “Stop Asking Me to Empathize with the White Working Class: and a few other tips for white people in this moment” and a current call for a Meeting in the Ladies Room offer important perspectives, as does Yolanda Pierce’s lament about the state of an already-fragile hope for racial and gender justice. Pay attention to brother Van Jones, who is truly out there doing God’s work, and making a sustained, deep effort to get at what really divides us.

In the meantime, please stop assuming, listen attentively, and look deeply within yourselves to purge racism and sexism (and a whole litany of other ‘isms). Most significantly, get yourselves together. And in so doing, remember that black bodies have historically been your solace in a myriad of ways. Embrace this opportunity to dismantle oppressions.

Ashes to ashes,

Dust to white liberal feminism.

LeRhonda S. Manigault-Bryant is Associate Professor of Africana Studies at Williams College. She is the author of Talking to the Dead: Religion, Music, and Lived Memory among Gullah/Geechee Women (Duke University Press), and co-author of Womanist and Black Feminist Responses to Tyler Perry’s Productions (Palgrave Macmillan) with Tamura A. Lomax and Carol B. Duncan. Follow her on Twitter @DoctorRMB.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.