The Importance of Sarah Forten’s Abolitionist Poetry

Depictions of slavery in the United States have captivated audiences for centuries. In honor of the recent National Poetry Month and the ascendance of youth activism in the era of Black Lives Matter, I thought it would be appropriate to center the role of an important youth poet whose abolitionist-poetry taught audiences about the brutality of slavery. The portrayal of separation is a useful theme through which poetry helps us to understand slavery. Dissociative violence, defined as the constant threat and/or manifestation of dissociating the enslaved from familial connections, was an often employed mechanism of control during enslavement. From 1831 to 1836, Philadelphia’s Sarah Forten was perhaps the most exemplary of the abolitionists-poets because she refined the use of poetry as a means to rouse sympathy for the enslaved.

Forten descended from a family of abolitionists whose political activism was central to Philadelphia’s Black community. Her father, James Forten Sr., was a wealthy sailmaker and abolitionist as well, and his impact extended beyond Philadelphia. James financially contributed to The Liberator, an upstart Boston newspaper founded January 1, 1831 by white abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. While Forten was an active member of both the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society and Female Literary Association, her writings in The Liberator helped greatly in making visible Sarah Forten’s work to non-Philadelphians. Her writing career began at the age of seventeen when she published in The Liberator’s January 22, 1831 issue a poem entitled “The Grave of the Slave” under the pseudonym “Ada”.

“The Grave of the Slave” evoked how wretched the institution of slavery was and why, to the enslaved, “The grave to the weary is welcomed and blest” because in “death, to the captive, is freedom and rest.” Only in death, she proclaimed, could the enslaved person finally gain true freedom. Forten and the rest of the growing abolitionist movement of the 1830s fought to secure freedom for the enslaved while they were alive. The common thread of all abolitionist writing was a moral appeal to potential supporters, and Forten’s poetry allowed her to express to her readers specifically what they were fighting against.

Abolitionists not only fought for emancipation, but also fought against the cruel effects of slavery on the bodies and minds of the enslaved. Maiming the body was one thing, but the psychological warfare of slavery was another ordeal. Not fully being able to protect your family from separation was an important theme in Forten’s poetics of dissociative violence. In “The Slave Girl’s Address to Her Mother,” she portrays an enslaved girl and her mother being separated from their family. Forten describes the daughter’s pleas for her mother to “weep not, though our lot be hard,” because though “we are helpless-God will be our guard.” The daughter calls on God as the being who will keep them safe in an unsafe world. Their conversation continues when the daughter harkens back to God “For He our heavenly guardian doth not sleep” since “He watches o’er us-mother, do not weep.” The daughter believes in the hand of God eventually working on their behalf while in bondage. She also later projects a microscope onto white America when she says “Oh! ye who boast of Freedom’s sacred claims/-Do ye not blush to see our galling chains.” Slavery’s continuance meant when America boasted to the world of its great democratic ethos, it did not have Black persons in mind.

Although Sarah never felt slavery’s chains, her words were a form of solidarity toward enslaved members of her race. It is not as if free Black northerners were unaffected by slavery; northern segregation was directly connected to white supremacy’s reign that allowed for southern slavery’s pervasiveness. What was most profound for me was reading how Forten narrated the psychological effects on the enslaved; how the enslaved felt having to hear “that sounding word-‘that all are free’” while whites did not care to listen to the thousands who “groan in hopeless slavery?” In Forten’s interpretation however, she claims “in thine own time deliverance thou wilt give,/ And bid us rise from slavery, and live.” Faith was one of the centerpieces of Forten’s poetry, and position and identity aided her in not wading in despair despite the enslaved population doubling from her birth in the mid-1810s to the early 1830s. Abolitionism was a social movement that needed important voices like Forten’s to rouse public sentiment on behalf of the disinherited enslaved population.

In potentially her most captivating poem, “The Slave Girl’s Farewell,” Forten constructs a scene of a young girl being separated from her mother in the West Indies, and taken to Louisiana by her enslaver. She tearfully says to her parent “Mother, I leave thee-thou hast been[.] Through long, long years of pain [.] The only hope my fond heart knew; Or e’er shall know again.” The daughter grapples with the magnitude of the moment at which the mother who cared for her all of her life will not be there anymore. In their waning moments together, the reality of the moment dawns on her when she realizes “Who now will soothe me at my toil/ Or bathe my weary brow?/ Or shield me when the heavy lash/ Is raised to give the glow?” While tearing up, she continues by saying “Think of me, mother, as I bend/ My way across the sea;/ And midst thy tears, a blessing waft,/ To her who prays for thee.” The pain of constructing and writing such tragic occurrences was potentially why, while writing prose, she wrote boldly about American hypocrisy.

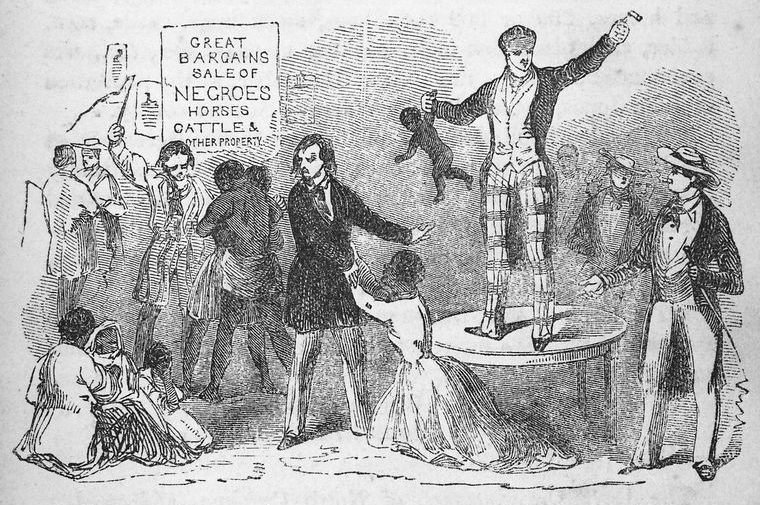

The theme of American hypocrisy was also found in her “The Abuse of Liberty” editorial as well. In it, Forten dubs the United States as unmatched in “the wide-spread canopy of Heaven in its abuse of man’s liberty.” Her perception came from America’s lofty goals of “life, liberty, and happiness” being only for white men. Yet, most of the wealth of the nation came from the enslaved population of the land. This hypocrisy manifested itself most through depriving enslaved persons of familial security. Wealth driven from the lucrative domestic slave trade fueled familial insecurity, especially as Forten grew into her womanhood. According to historian Edward Baptist, in the 1820s alone approximately “35,000 enslaved people from Maryland and the District of Columbia; 76,000 from Virginia; and 20,000 from North Carolina” were taken to the new southwestern states. Those numbers illustrate the reality which Forten’s poetry attempted to animate for her audience. This reality made Forten question whether her race’s skin color was the sole reason “that they are to bow beneath the lash, and with a broken, bleeding heart, enrich the soil of the pale faces?” Forten invokes a socioeconomic critique of slavery where the enslaved are making money for the enslavers while whites benefit socially from their illegitimate wealth and status. Dissociative violence illustrated how separating the enslaved from the wealth their bodies generated was so troublesome. Beginning at the age of seventeen, Forten wielded her poetic voice to describe the horrors of slavery in ways others could not.

Forten’s age while maturing into her role as a public abolitionist-poet should not be undervalued, nor should the important connection between her activism and the power of Black youth activism in American history. In light of the recent March for Our Lives protest in Washington D.C. after the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting, one may believe that moment was unique; this is false. As mentioned prior, Forten’s abolitionist-poetry career began at seventeen in 1831; at twenty-one in 1883, Ida B. Wells sued a train conductor with the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad Company for failing to honor her ladies-only ticket; and in January 1973, Black students at Escambia High School in Pensacola, Florida, boycotted days of school over the use of Confederate iconography on campus. These examples show how Black youth activism existed long before the present iteration in The Movement for Black Lives or March For Our Lives. They are extensions of the youth activism present in the short-lived abolitionist-poetry career of Sarah Forten. Forten’s dynamically poetic accounts of slavery’s depravity depicts how powerful a tool poetry can be at heightening the consciousness of audiences.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Great article! I’m writing my dissertation on Sarah Forten‘s niece, Charlotte Forten, during her teenage years in Salem. Interesting fact: Sarah Forten’s “Grave of the Slave” was set to music by Frank Johnson & sung at Anti-Slavery events.

Thank you much for your kind words Kristen! I loved learning about Charlotte for my MA thesis. She is such a fascinating figure!

I forgot that “Grave of the Slave” was set to music! Such an important point to make! I would love to hear more about your dissertation topic because I wrote a bit on Charlotte for my thesis.