The Education of Black Boys

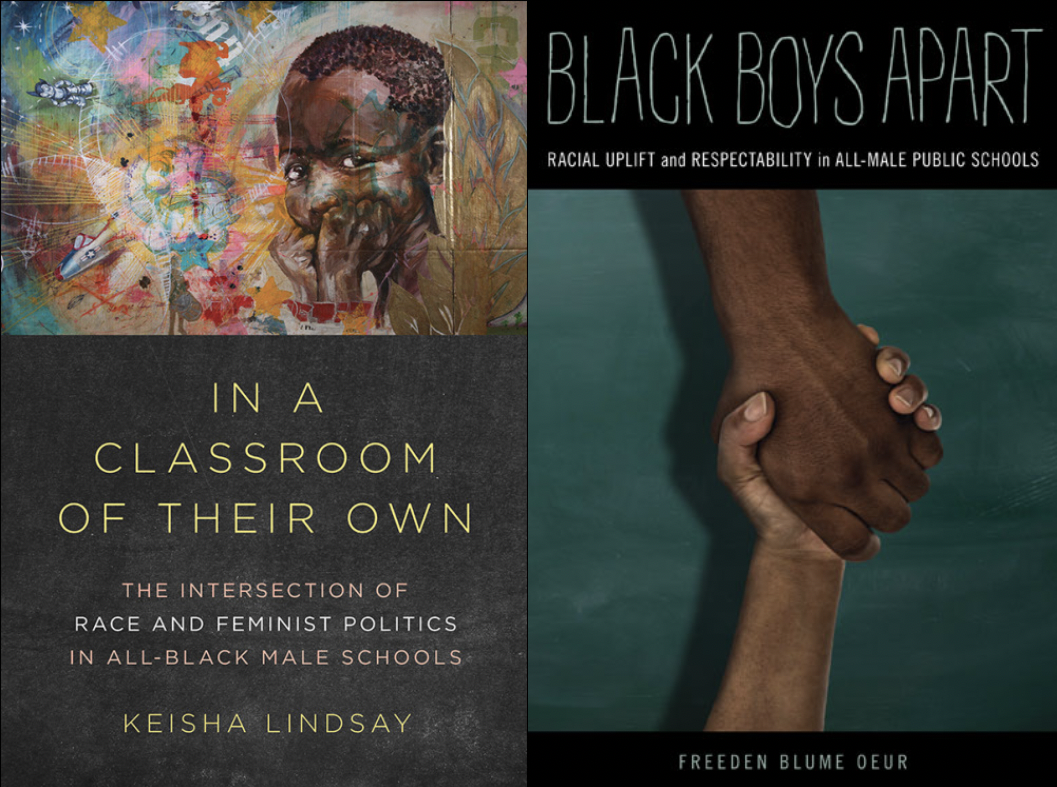

In both Keisha Lindsay’s In A Classroom Of Their Own: The Intersection of Race and Feminist Politics in All-Black Male Schools and Freeden Blume Oeur’s Black Boys Apart: Racial Uplift and Respectability in All-Male Public Schools, the schooling of Black boys is examined and critiqued with care and humanity. Each takes a timely, yet sensitive look at single-sex education and asks what is jeopardized and gained by parsing the issues facing Black boys from those facing Black girls.

Through a discourse analysis of written documents about all-Black male schools (ABMS), Lindsay sets out to present “a work in political theory with a heavy insistence on practice” (5). This book critiques explicitly how proponents of ABMSs endorse an anti-racist and anti-feminist approach to educating Black boys that simultaneously obscures and oppresses the education of Black girls. The author meticulously lays out an argument on how the politics of experience builds discursive dialects—the contradictory reality that social groups’ appeals to experience are mired in a politics that is both emancipatory and oppressive—that positions Black boys as the victims of racist and overly feminized classrooms. This approach, the author argues, is deficient and flawed. While anti-racist, it is antifeminist and harms boys and girls—not just one segment of the population.

Powerfully, the book also theorizes how supporters of ABMSs and feminists can build progressive collations to address and improve the well-being of Black schoolboys that “is not separate from but intrinsically linked to doing the same for Black girls” (120). What works about Lindsay’s endeavor to examine structures of power around the ABMS movement, is it is not a condemnation or a “call for moratorium” on this educational intervention, but a challenge to both Black male supporters and feminist activists to rise above their experiential politics, to embrace a normative-critical understanding of power, and to embrace self-reflectivity.

Blume Oeur (2018) utilizes an ethnographic approach to examine the societal significance of single-sex education. Through extended case method the author studied two predominately Black all-male public schools, which included observations inside and outside of class over eleven months and one hundred fifty interviews (students, parents, teachers, administrators, and school district officials). Drawing on Michel Foucault’s notion of governmentality, this work draws connections between the goals of all Black male schooling and traditional notions of Black manhood—W.E.B. Du Bois’s ideas of the “Talented Tenth” and respectability politics specifically. The text outlines that while proponents sketch all Black single-sex schools as innovative, they “revise old notions about Black male reform” (15), and “freeze” early Du Boisian theory for their gain. The author’s observations and interviews reveal that building the foundation of Black all boy schools on the respectability and racial uplift through resilience lacks consideration of Du Bois’s later work. In turn, the school environments institutionalize respectability, promote hegemonic masculinity, and poses harm through intra-racial division across class and gender.

Like Lindsay, Blume Oeur does not aim to condemn or stifle single-sex educational interventions for advancing Black boys, yet poses a constructive critique that acknowledges a need to create a Black feminist alliance. To this end, the text proposes Du Bois’s theory of abolition democracy as an approach to advance Black boys that also rejects domination and embraces a full spectrum of Blackness and masculinities.

My chest tightened as I began to read In A Classroom Of Their Own and Black Boys Apart. As a mother of two Black boys, I am keenly aware of frightening circumstances that face them in the classroom, yet as a Black feminist I understand—through experience and my scholarship—that these circumstances are no less terrifying for Black girls. The anxiety I felt in the firsts pages of each book stemmed from the reality that problem-solving critical issues facing Black children in public education cannot sacrifice one group for the other. To my relief, each of the authors acknowledged these issues and attempt to address the underlying threads of power that could ultimately condemn the efforts of single-sex education.

Both texts grapple with a problem that has long plagued the African-American community from a big-picture perspective by turning, first, to Black intellectual histories. For Lindsay it is Black feminisms, and for Blume Oeur it is the evolved works of Du Bois. The examination of intellectual history as a starting point is essential for theoretical innovation for such issues. First, our intellectual past is a clear map toward our future. With an issue such as education—a tool regarded as a key to freedom within our culture—there are far too many texts and intellectual works from which to draw both courage and solutions. This is where both books get it right.

Second, as it pertains to disrupting power for full liberation—which is the expressed aim of schools examined in each book—both authors embrace Black feminist theory as a means to explain the ways power takes shape and how we might move forward. Lindsay does so by centering the works of E. Frances White, Deborah King, Kimberlee Crenshaw, Patricia Hill Collins, and Assata Zerai, to name a few. Blume Oeur concludes his book by drawing on the Black Lives Matter movement—with its anti-respectability politics and decentralized power structure—as an inspiration of how we might sow “the seeds of the counter-hegemonic struggle that Du Bois envisioned” (172). Embracing Black Feminist theory ensures that the solutions we devise for improving the education of Black boys does not also erase Black girl and non-binary students.

Inserting the notion of endangered masculinity at the center of the issues facing Black boys in public education erases Black girls from the “solution” and disserves the intellectual development of Black boys. In A Classroom Of Their Own and Black Boys Apart confront issues of power and domination within Black all-male education with care and reverence to Black intellectual history. Ultimately, each turn toward theories of possibility that refuse to erase Black girls and, thus, fight for the fullest humanity of Black boys.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

i attended an all-male, majority black high school. it was indispensable to my development, as a human being and as a young man. the exclusion of girls in no way demeaned black women or created some sort of animus toward them. black boys require different nurturing than black girls. they need to be prepared for this painful vagaries of this world. that preparation must be practical, not conceptual or ideological. these topics are great for publishing academic books, but they have no true bearing on how to actually raise black boys. i highly recommend all-male school for black boys. i have a law degree from howard and a ph.d. from penn, so i’d say it worked for me. feminist theory can be great, but we have to acknowledge its practical limitations.