Panama in Black as an Offering: An Author’s Response

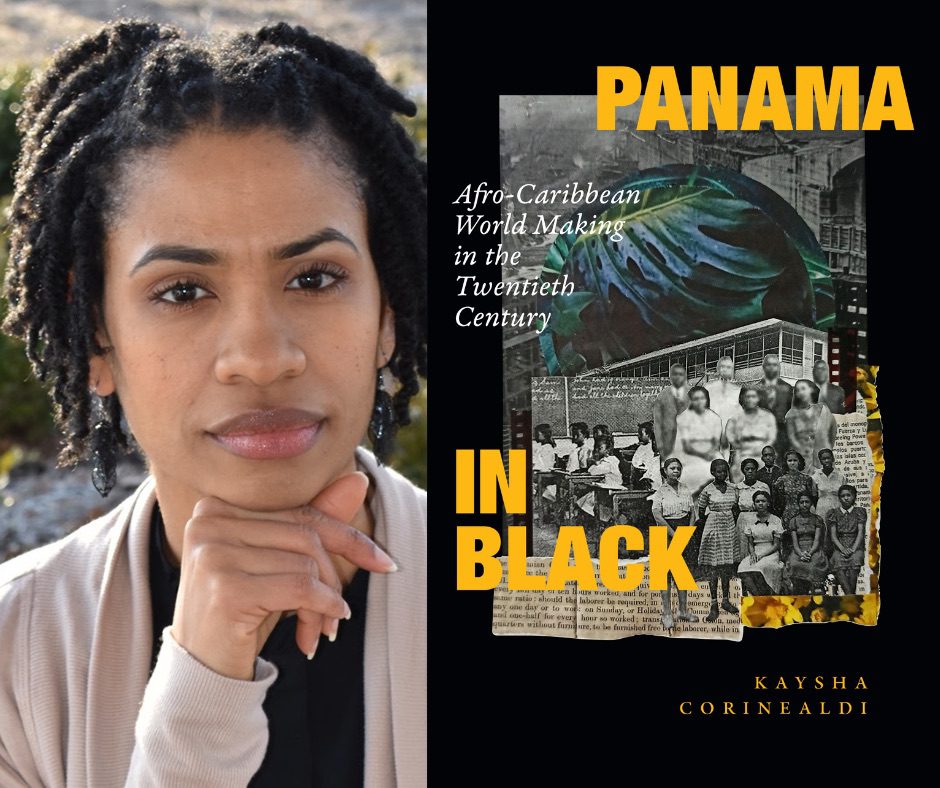

This post is part of our online roundtable on Kaysha Corinealdi’s Panama in Black.

When I started writing Panama in Black I imagined that it would be of interest to scholars of Black Studies, Central American and Caribbean History, and American Studies. I also assumed that those reading it might focus on the book’s specific contributions to Panamanian history and U.S.-Panamanian relations. As I finished the book I realized that these framings were but a beginning. I had a great deal to say about the role of education (as a political praxis and a communal experience), gendered policing within activist spaces, hemispheric anti-Black policies and their links to U.S. empire, and the impossibly high price of citizenship rights for Black people in the world. This evolution in my thinking is what informed the ideas of local internationalism and diasporic world making that ultimately shaped the book. These ideas were drawn from the life experiences of the men and women I followed in the book. People like Sidney Young and Esmé Parchment, who I could not neatly place within a specific national history. People like Leonor Jump Watson, Robert Beecher, and Anesta Samuel who imagined what was possible even as they were routinely made to believe that there was no hope and no alternatives to dehumanization. I thank Sharika Crawford, Maya Doig-Acuña, Marcus Johnson, and Paul Joseph López Oro for their generous engagement with my work as part of this book forum. Their reflections not only provide me with an opportunity to re-trace the evolution of my writing, but also expand the frame for discussing the goals and reach of Panama in Black.

Of the rich observations made by my interlocutors during this book forum, their attention to three specific approaches particularly stand out: the decentering of the Panama Canal and a focus on the afterlives of migration, continuing and expanding the model for discussing hemispheric Blackness, and exposing gendered hierarchies while highlighting the political acumen of Black women. In writing Panama in Black I benefited from a robust scholarship on Afro-Caribbean migration to Panama for the building of the Canal and the role of U.S. empire in dictating the terms of construction and creating a system of Jim Crow in the U.S. Canal Zone. The work of scholars like Velma Newton, Gerardo Maloney, Melva Lowe de Goodin, Olive Senior, Michael Donoghue, and Julie Greene, to name a few, had paved a formidable path. With Panama in Black I focus on what happens after the building of the canal, once those who toiled to build the canal were viewed as expendable, and their children and grandchildren were left to navigate the hostile reality of xenophobia and racism at national and imperial levels. How they dreamed, hoped, and built community, is at the core of my analysis.

In centering on this post-construction moment, I also, as saliently noted by Doig-Acuña, purposefully place attention to anti-Blackness as perpetuated by the Panamanian state. Anti-Blackness united Panamanian and U.S. officials, as well as a cross-class base in Panama, in their efforts to marginalize and silence Afro-Caribbean Panamanians. In focusing so extensively on the intricacies of laws, legislations, and community mobilization within Panamá City, Colón, and the Panama Canal Zone, I, as noted by Crawford, do not directly discuss how Afro-Caribbean migrants and their descendants in other parts of Central America and the Caribbean navigated similar attempts at alienation. Part of this was intentional. Scholars such as Ronald Harpelle, Asia Leeds, Lara Putnam, Glenn Chambers, Douglas Opie, and Jorge Gionavetti-Torres have provided us with rich studies on these very questions. But more specifically, I needed to highlight the unique aspects of what transpired in Panama. I found no records of other nations in the Americas that, in the 1940s, opted to denationalize the children of Black migrants. Additionally, in terms of numbers alone, more Afro-Caribbean descendants called Panama home than any other Central American nation. How many within and outside of academia knew this, I wondered? How many fully appreciated the extent to which by the mid twentieth century Panama was the heart of a robust Afro-Caribbean diaspora?

In dedicating much of the book to describing Afro-Caribbean community building in Panama, the Canal Zone, and the United States, I also sought to highlight cross-border and cross-linguistic collaborations between Black people across the hemisphere. These collaborations, as observed by López Oro, attempt to circumvent the logics of nationalism by making use of, but not depend on, the nation state. Building bridges across the Afro-Americas was a goal shared through the twentieth century and was manifested by moments like the creation of the Panama Tribune in the 1920s, Paul Robeson performing solidarity concerts in 1940s Panamá City on behalf of Afro-Caribbean Canal Zone workers, a Congreso de la Cultura Negra de las Américas first held in Colombia in 1977, then in Panama three years later, the formulation of Amefricanidade by scholar activist Lélia González in the 1980s, and continues to this day with organizations like La Red de Mujeres Afrolatinoamericanas, Afrocaribeñas y de la Diáspora. Hemispheric collaborations, especially when there are citizenship hierarchies involved, nonetheless require a naming of these hierarchies, and a commitment to not privilege one nation, language, or lived experience. These collaborations are messy but, as I explore in the book, are filled with potential. They require imagination. The very kind of imagination found in creating a community library, in organizing working people amidst anti-union policies, and in connecting educators and organizers that share an investment in Black life.

While centering the imagination required to create hemispheric collaborations, in Panama in Black I also address the gendered hierarchies that threatened to shortchange these collaborations. As noted by Johnson, López Oro, and Doig-Acuña, this focus is intentional, and breaks with earlier scholarship on Afro-Caribbean Panamanian history while building on a feminist archival practice. In assessing the work of the Panama Tribune, for example, I reflect on Amy Denniston’s brief period as editor for the paper. How might the newspaper’s Black internationalist praxis have expanded, I ask, if Denniston had remained as editor and continued writing and publishing the work of other women that linked Panama to Jamaica, challenged monolingualism, and promoted professional co-education? What could men like Sidney Young and George Westerman have learned if they had listened to their women peers? What would it mean to see these women as equals in matters of community leadership and organizing? Examining the work of educators like Leonor Jump Watson and the women who came together to form Las Servidoras allowed me to partially answer these questions. Black world making as lived and promoted by these women was multi-generational in nature, required developing new vocabulary around citizenship, belonging, and pride, upheld the history of women as leaders, and created new traditions in inhospitable spaces. Yet, hierarchies of class, propriety, language, and professional attainment, affected communal efforts led by women and men alike. For me this was an important reminder that undoing patriarchy, anti-Blackness, and legacies of exclusion is difficult work.

In writing Panama in Black, I did not want to promote the notion of an ideal or non-problematic way of doing or studying Black activism and community building. My articulation of Afro-Caribbean diasporic world making focuses on Black people taking risks, sometimes leading to success and other times to disappointment and a period of self-reflection. Foremost, this articulation requires understanding that even at the lowest point of despair and uncertainty, this world making triumphed against a version of the world that categorized Black people as disposable. For current and future readers of Panama in Black, my hope is that you see the book as an offering and an opportunity to think about what it means for Black people to dare to dream, in imperfect but poignant ways, about a world centered around the potentials of Black life.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.