Julia W. Garnet’s Civil War Activism

Throughout the American Civil War male proponents (Black and white) of mobilizing United States Colored Troops (USCT) regiments viewed military service and spaces as exclusively male. USCT enlistment rhetoric routinely claimed that Black military service (and sacrificing one’s life) would “prove” Black manhood and would result in Black men receiving public adulation from white society. At the same time, many advocates of USCT enlistment either ignored or downplayed the fact that Black military service also provided Black women with opportunities to restructure gender ideology. Black women (such as Emilie Frances Davis) made sacrifices that were critical to the US’s wartime mobilization efforts and Black people’s aspirations for a more racially inclusive society that included destroying the institution of slavery.

When male USCT proponents did mention Black women in connection with Black military service, it was primarily to emphasize their role as recruiters within their communities. During an 1863 recruiting event in Philadelphia, Pennsylvanian Congressman William D. Kelley spoke publicly to Black women about the “dangers” of engaging in intimate relationships with Black men who “avoided” enrolling in USCT regiments. The Weekly Anglo-African (a New York City-based Black newspaper) proclaimed “Let our maidens vie with each other in urging the young men forward to their duties.”1 These statements, by both Black and white men, highlight their limited understanding of the prominent and diverse roles that Black women provided to the US war effort before and throughout Black soldiering.

Northern Black women knew long before President Abraham Lincoln and the US Government that the Civil War was a conflict centered on human rights issues, along with their simultaneous demands for racial and gender equality. Black women’s socio-political activism publicly demonstrated a nuanced understanding of the war’s profound and damaging impact on various Black communities. Black women joined the Underground Railroad or religious organizations to protect the lives and rights of numerous Black refugees as they sojourned to their new living situations.

In New York City Black women received public adulation in 1862 for organizing the Ladies Calico Dress Ball, which produced a sizeable contribution for the Home Committee of the National Freedmen’s Relief Association in Port Royal, South Carolina. Black women across the nation organized similar efforts to advocate for the lives and rights of enslaved and newly freed people. Additionally, many Black women worked diligently with Vigilance Committees or by themselves to protect the freedom and safety of Black people—freeborn and freed—from becoming potential victims of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, a federal law that made any Black person a potential victim of slavecatchers in slave states or beyond. Northern Black women persistently fought to protect lives and assure the civil rights of Black people.

Months after Lincoln’s January 1863 Emancipation Proclamation officially changed the US Government’s war from one to preserve the Union, to one intent on ending slavery, large-scale racialized violence towards Black people was, sadly, still common in the North, where slavery was illegal. In New York City during the Civil War, draft riots resulted in the deaths of numerous Black people and the destruction of their homes, businesses, and institutions. Seven months later the mobilization of the Twentieth United States Colored Infantry (USCI), primarily in New York City, successfully pushed onward thanks to the support of Black women, such as Julia Williams Garnet.

Julia’s fight against various forms of racial and gender discrimination began in her birthplace of Charleston, South Carolina. Being born free did not exclude her, or any Black person, from having to live in a society where one’s race (over anything else) defined one’s lived experiences in America. Even after her family relocated to Boston, Massachusetts, Julie realized that anti-Blackness was not a Southern anomaly, but that it permeated every aspect of society in the North too. In order to combat various forms of oppression, Julia became a prominent and active member of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society by the 1830s in addition to working as an educator. Her activism persisted over years, and the Civil War provided her (and many other Black women) with new avenues to continue fighting against her oppressors.

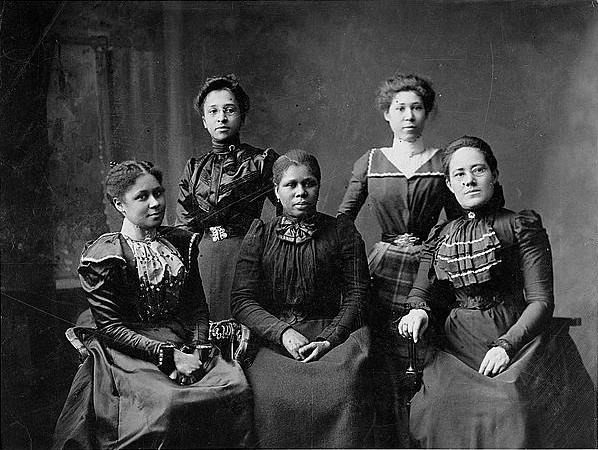

After the public fervor and passionate pageantry of recruiting Black men into the Twentieth USCI dissipated, Black New York recruits discovered numerous harsh realities during their training. Neither the US War Department nor the Union League Club of New York (a white-male organization that raised funds for all of New York USCT regiments) desired the bodies of Black men and did not provide them with the resources recruits needed throughout their training. When the US Army failed to supply nutritional diets to newly mobilized New York USCT recruits, forty Black women took it upon themselves to establish the Ladies Committee on January 25, 1864, with Julia Williams Garnet as their president to address this glaring issue at the military camp.2 It is important to note that the organization’s name (similar to the previously mentioned Ladies Calico Dress Ball) was a symbolic and public assertion that they were patriotic and self-sacrificing women worthy of respect while demonstrating that “lady” was not a racially exclusive word reserved for white women.

Many historians privilege the efforts of white women for publicly asserting that patriotism was never exclusively male. Such a limited approach ignored the importance and nuances of Black women’s gendered reframing of wartime support and activism. It is long overdue for Black women such as Julia Williams Garnet to receive more recognition—by academics and the public—for the influential role that they and their communities played in the US winning the Civil War.

Great read!!!