Black Rebellion and the Political Imaginations of African American Teachers

Nat Turner became an impromptu topic of discussion in my third grade classroom. Ms. Todman had a way of getting her point across that seared it into your mind. She was an older Black woman from North Carolina, teaching at a Black parochial school in Compton, California during the 1990s. We were not taking our task seriously as we prepared for our school’s annual Black history month program. The assignment was to memorize Eloise Greenfield’s poem about Harriet Tubman running in the dead of night to escape bondage, and then returning time and time again to guide others on their path to freedom. The performance included one of my classmates dressing up as Tubman and performing a dramatization of the words we spoke in unison. Ms. Todman explained there was a world so hateful toward Black people that many who came before us gave their life to fight for even the smallest joys we have today. We had to remember these people, to honor their bravery and put some part of it into practice in our lives. Nat Turner wasn’t just killed after his revolt, she stressed. They even took parts of his body as trophies, made clothing accessories from his skin. I remember thinking she must have exaggerated this story. But even if only a fraction of it was true, her point was well taken.

Ms. Todman’s engagement with radical aspects of Black political history, namely historical figures that were willing to respond to Black oppression with violent rebellion, was not an isolated encounter. This trans-curricular moment earmarked a consistent line of thought in the pedagogical history of African American schoolteachers. Black educators historically deployed radical Black historical narratives to stretch students’ imaginations about the possibilities for social transformation. This is most prominently captured in African American teachers’ representation of historical characters such as Tubman, Turner, and Toussaint L’ouveture in textbooks they wrote during Jim Crow.

Black Jim Crow teachers are often represented as middle class, bourgeoisie professionals, beholden to the politics of respectability; implying that an appreciation of Black violent rebellion against white supremacy was outside the purview of their pedagogy and imaginations. However, their political ideologies were much more complex than this flattened narrative suggests. In their own intellectual traditions we see them also representing, in celebratory fashion, some of the least respectable figures (as measured by mainstream social standards of the time)–or, perhaps their enactment of the politics of respectability was more malleable than popular understandings of the term make room for. Certainly their celebrations of Nat Turner and assertion that “he was, undoubtedly, a wonderful character” was not intended to convince white spectators of his, or their, civility.

Textbooks written by African American teachers as early as 1890 represented the story of Nat Turner and the Southampton Insurrection of 1831 in heroic fashion. Between 1890 and 1922, there were four textbooks written by scholars who also taught in public schools. Edward Johnson, who was born enslaved in North Carolina, published A Short History of the Negro in America in 1890. Leila Amos Pendleton taught in Washington D.C. public schools and published A Narrative of the Negro in 1912. John Cromwell a formerly enslaved man who also taught in D.C. published The Negro in American History in 1914. Carter G. Woodson was a schoolteacher for nearly thirty years and published seven different textbooks. His first textbook, The Negro In Our History, was published in 1922 and became the most widely circulated of any that preceded it.

Nat Turner’s story was not the only narrative of slave resistance presented in Black teachers’ textbooks. They all explore the Haitian Revolution and wide reaching accounts on the genealogy of Black resistance to slavery. Writing specifically about the United States, Carter G. Woodson offered, “The most exciting of all these disturbances did not come until 1831, when Nat Turner, a Negro insurgent of Southampton County, Virginia, feeling that he was ordained of God to liberate his people, organized a number of daring blacks and proceeded from plantation to plantation murdering their masters.”

All four educators represented Nat Turner as honorable and highly intelligent. Edward Johnson emphasized that Turner was “a prodigy” amongst his people. Leila Pendleton took care to note that Turner “never had the advantages of education” yet there were few men that surpassed him “for natural intelligence and quickness of apprehension.” In a less laudatory fashion, Woodson also observed details about Turner’s intelligence, emphasizing the shock among white southerners that enslaved Blacks had the capacity to organize a revolt of such a scale.

These teachers did not shy away from discussions of violence in representing the story of Nat Turner. At times the narrative is even presented in epic fashion. John Cromwell provided vivid descriptions of specific incidents:

Armed with a hatchet Nat entered his master’s chamber and aimed the first blow of death but the weapon glanced harmless from the head of the would-be victim, who then received the first fatal blow from Will, a member of the party, who without Nat’s suggestion got into the plot. Five whites perished here.”

With the exception of Woodson’s textbook, Nat’s companion Will is given special attention in all accounts. By Johnson’s measure, Will “was a giant of a man, athletic, quick, and ‘best man on the muscle in the county.’” According to Pendleton, Will died in heroic fashion: “Will armed himself with a sharp broad-ax and with it killed several people. When the militia arrived he would not surrender, but fought to the last and when dying asked that his ax be buried with him.” Though Woodson was more reserved in his writing, evidence of his attempt at objectivity as a Harvard trained historian, he included an image of a slave insurrection entitled “The Negro Calls a Halt.” Thus, in absence of the spectacular accounting provided by his predecessors, Woodson offered students the opportunity to envision the scene of this insurrection in ways that the written text did not.

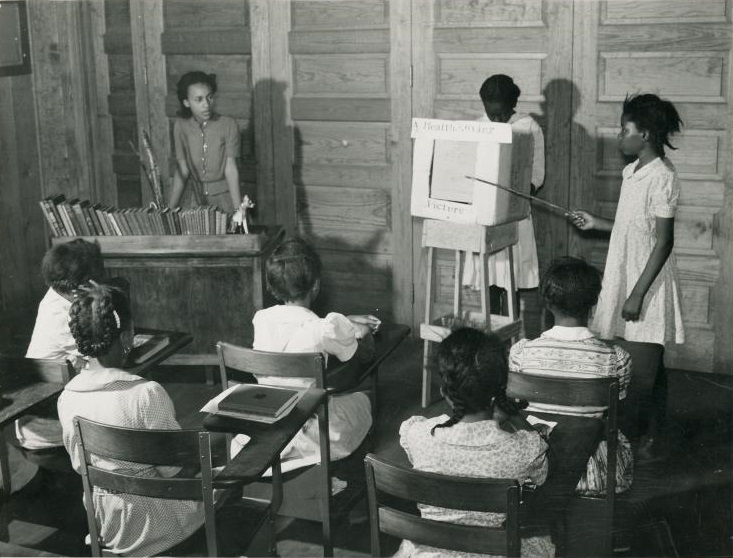

As the previous example demonstrates, radical narratives in Black political history were not only confined to the written text in African American education. Given the strong emphasis on performance and recitation in Black school culture, various mediums were used to convey this history and set of ideas to students. For instance, as early as 1864 we find accounts by teachers like Charlotte Forten Grimké, an African American teacher in South Carolina reporting that she relied on oral traditions to teach her students about Toussaint L’ouveture: “After the lessons, we used to talk freely to the children, often giving them slight sketches of some of the good and great men…I told them about Toussaint, thinking it well they should know what one of their own color had done for his race. They listened attentively, and seemed to understand.”

Beginning in the 1920s, Carter G. Woodson printed and circulated decorative materials reflecting Black history and culture to be hung up in classrooms and school auditoriums. One of these posters was an illustration of Harriet Tubman. This was not the popular image of Tubman, neatly clad, poised and standing aside a chair. It was an illustration by James Lesesne Wells, a professor at Howard University, depicting Tubman hoisting her most prized companion—her rifle—while pointing a group of fugitive slaves in the direction of their freedom. Some schools even staged reenactments of the Haitian Revolution for school plays during Negro History Week in the 1940s. Years later, a school organized in Nashville by members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) staged a skit based on Turner’s insurrection in 1967, after local authorities evicted them. Historian Russell Rickford noted, “In a display of defiance, its faculty staged a skit based on Nat Turner’s 1831 Revolt, a production that required students to pretend to hack white slaveholders to death.”

No generalization can be made to suggest all Black teachers taught their students about Nat Turner or with any level of consistency. These cases of Black teachers publishing textbooks are extraordinary. However, what these cases do suggest is that there was a consistent body of thought among African American teachers to push for a radical representation of Black history that challenged white supremacy, even the parts of history that caused dis-ease for white people. As Charles Wesley wrote, this was a “heroic tradition” that formalized in the 19th century: “heroes of freedom had been denounced by most white Americans as demented and deluded, but now they were to be, by new standards bold Negro-Americans, who were heroes of history.” Teachers were central to this Black intellectual praxis.

Engaging radical aspects of Black political history became an opportunity for students and teachers to engage in a shared critique of their Jim Crow confinement. It also indulged a persistent desire for redress (even revenge) on the part of Black communities (re)encountering the trauma wrought by white supremacy. Even as African American teachers navigated constraints imposed by white Jim Crow school authority, they were also forging an interior world in their own souls and the minds of their students, through their writing and in the private spaces of their classrooms.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Black resistance to racial oppression was omnipresent in many of the classrooms and pews of Black schools and churches. Prof. Givens has provided great insight into the ways in which Black teachers, contrary to popular assumptions, promoted that resistance in the minds of their students that built up over time and culminated in the modern freedom struggle. My maternal grandfather who did not advance beyond eighth grade passed on these lessons that he learned from his teachers in segregated southern schools. His stories sparked a curiosity about Black History that influenced my trajectory socially, politically, and intellectually. Thanks for this fine piece that reminded me of my grandfather and that should remind us that like the river described by Vincent Harding, the struggle ebbs and flows, takes unexpected turns, but continues inextricably toward freedom.