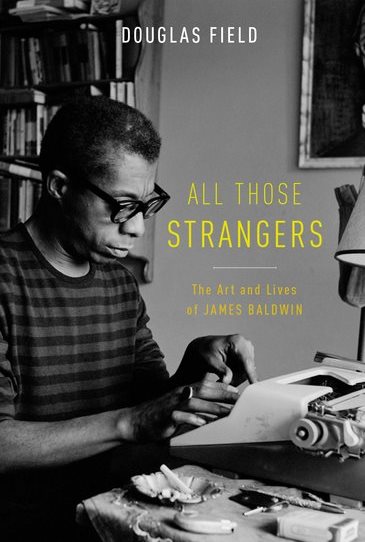

The Art And Lives of James Baldwin: An Interview with Douglas Field

This month I interviewed Douglas Field about his book All Those Strangers: The Art and Lives of James Baldwin. Field is a professor at the University of Manchester, where he teaches in the Department of English and American Studies. He received a PhD from the University of York in English Literature. He sits on the Editorial Committee of Manchester University Press and is the co-founding editor of the James Baldwin Review, an annual peer-reviewed journal published by Manchester University Press. He is a former managing editor of Modernism/ Modernity and a former book review editor of Callaloo. His previous books include A Historical Guide to James Baldwin and James Baldwin.

This month I interviewed Douglas Field about his book All Those Strangers: The Art and Lives of James Baldwin. Field is a professor at the University of Manchester, where he teaches in the Department of English and American Studies. He received a PhD from the University of York in English Literature. He sits on the Editorial Committee of Manchester University Press and is the co-founding editor of the James Baldwin Review, an annual peer-reviewed journal published by Manchester University Press. He is a former managing editor of Modernism/ Modernity and a former book review editor of Callaloo. His previous books include A Historical Guide to James Baldwin and James Baldwin.

Phillip Luke Sinitiere: Your title invokes James Baldwin in the plural, which emphasizes the contested terrain about his influence, impact, and legacy. Can you comment on this in light of your book’s main argument?

Douglas Field: Baldwin has always struck me as someone who never stood still—he was a self-styled transatlantic commuter who lived in France and Turkey, and traveled across the globe; in terms of genre, he was a short story writer, novelist, playwright, and poet. His writing repeatedly resists fixity, which Baldwin, I think, sees as dangerous because it fails to engage with complexity, such as the perennial binaries of black-white, gay-straight good-bad, etc. Racial problems will persist, Baldwin said, if “white” people continue to believe they are white.

Baldwin’s writing developed as he matured as a writer and his views changed. For this reason, I drew attention to the many Baldwins out there, a writer who means many things to many people. I wanted to move beyond academic criticism which claims Baldwin as queer or black, religious or secular, or as an essayist or novelist. If you hear what Baldwin says in his work, life is messy and chaotic: it’s rarely neat and ordered. Why can’t people be contradictory, confused, ambivalent, uncertain? Baldwin adroitly looked into the complexities of people’s lives, fictional and actual.

Sinitiere: Your book’s opening chapter maintains that it is important to view Baldwin’s early career Leftist affiliations as formative in his political development and vital to understanding the shifts in his perspectives over the course of his lifetime.

Sinitiere: Your book’s opening chapter maintains that it is important to view Baldwin’s early career Leftist affiliations as formative in his political development and vital to understanding the shifts in his perspectives over the course of his lifetime.

Field: I think this is in some ways linked to the first question in the sense that Baldwin’s political activity in his youth has been somewhat airbrushed out of critical and biographical accounts. Baldwin was active politically in his youth. He was in the Young People’s Social League. “I marched in one May Day Parade,” Baldwin recalled in No Name in the Street, “carrying banners, shouting, East Side, West Side, all around the town, We want the landlords to tear the slums down!” I’ve read letters where Baldwin is more explicit about this political engagement up to about the age nineteen. I am not claiming that Baldwin remained a committed Trotskyite but I wanted to shine a light into this area of his life, as well as his early book reviews. Baldwin cut his teeth as a reviewer in magazines associated with the New York Intellectuals, among them New Leader and Partisan Review. I think the magazines’ political engagement chimed with Baldwin. In later years, Baldwin became more suspicious of political affiliations but early years in the company of New York Intellectuals proved formative.

Sinitiere: Explore the connections you make in chapter 2 between literature, Black radicalism, state surveillance, and Black history.

Field: Historically, as Henry Louis Gates Jr., has argued, there is something innately political about African American literature. It has always been, implicitly or explicitly, a way of refuting the claims that people of African descent lacked capability of reason and imagination. Baldwin’s writings explicitly tear those claims asunder. Baldwin is in control; he mastered language and European culture, writing his way into the canon: “I write therefore I am,” as Gates puts it. But Baldwin threatened the white establishment, and chastised white liberals for not being conscious enough. And because he was a threat; because his writing was so persuasive, and because his speeches were so powerful, the FBI monitored him closely. Thanks to the path-breaking work of Bill Maxwell, we now know that J. Edgar Hoover held a particular fascination for African American writing, and for Baldwin in particular. Looking at Baldwin’s voluminous FBI files, it struck me that Baldwin knew the FBI was watching, but refused to change what he wrote about and refused to play along with the pressures of being surveilled. The FBI perceived Baldwin as radical in a formal sense, i.e. his connections to Malcolm X and the Black Panthers. However, the sheer volume of his FBI files—many more than Richard Wright—suggest that the FBI recognized the power of his writing and speech-making. He remained, as Baldwin put it, “a disturber of the peace.”

Sinitiere: In a chapter on Baldwin and religion, you contest the secularization narrative of his relationship to the Christian church: when he gave up the pulpit as a teenager, he became increasingly secular. How does your work on this topic add fresh perspective to our grasp of Baldwin and religion?

Field: When I started work on the book quite a few years ago, I was struck by how little scholarship focused on Baldwin and religion. Scholars and biographers cited his Pentecostal past and they wrote about the theme of Christianity in Go Tell it on the Mountain and The Fire Next Time, but few scholars seemed to look at the specificity of Baldwin’s Pentecostal past. I remember being struck by the work of Michael Lynch who looked closely at Baldwin’s depictions of religion. Lynch made the important point that it is reductive to dismiss Baldwin as “secular” since his work continues to engage with spiritual matters, even if outside of the institution of the church. I wanted to build on Lynch’s important work and to look at the ways in which Pentecostalism is as Robert Anderson describes it, “a kind of anti-Establishment Protestantism,” which makes sense in relation to Baldwin’s writing. I have no doubt that Baldwin fell out of love with the church as an institution, but I think his writing, right until the end, continued a dialogue and debate with the church. If he had been “secular,” as some scholars maintain, why carry on the conversation? If jazz was Ted Joans’s religion, then I think love became Baldwin’s religion. Love is such a central theme in his work. It is frequently imbued with spirituality and it’s again rarely discussed by critics who seem unsure how it can theorized or placed into critical alcoves.

Sinitiere: In chapter 4, you write, “Baldwin’s varied travel (and residence) abroad sharpens his observation of the society and culture in which he reached his maturity” (p. 116). How does All Those Strangers trace out Baldwin’s work in relation to Black internationalism?

Field: There’s something paradoxical about Baldwin’s writing. He claims on a number of occasions that travel helped him see America more clearly. “One sees [one’s country] better from a distance,” Baldwin stated in Sedat Pakay’s 1970 film From Another Place, “from another place, another country.” At the same time, little of his writing is about the places where he lived, aside from Giovanni’s Room, some short stories and some essays. Baldwin spent an interrupted decade living in Turkey but he published nothing about it, which is curious. Baldwin wrote essays about Paris but in many of them he refuses to romanticize the diaspora; he draws attention to the cultural and linguistic obstacles when he meets Francophone Africans in Paris, for example. In this way, I think Baldwin was very much ahead of his time. He anticipates the work of Brent Hayes Edwards in the Practice of Diaspora where he states that “black modern expression takes form not as a single thread, but through the often uneasy encounters of peoples of African descent with each other.” My aim was to tease out the uneasy encounters that Baldwin describes in his work while being careful about calling Baldwin a “transnational” writer, which is one of those zeitgeist terms which can be applied to most authors.

Sinitiere: As an author and editor of multiple works on Baldwin, you have a pulse on what’s happening in Baldwin studies. What does the future of Baldwin scholarship look like?

Sinitiere: As an author and editor of multiple works on Baldwin, you have a pulse on what’s happening in Baldwin studies. What does the future of Baldwin scholarship look like?

Field: The future of Baldwin scholarship looks very bright. The James Baldwin Review is going well. In terms of where things are heading, the sheer volume of critical work on Baldwin over the last fifteen years or so means that he has certainly been “recovered.” Scholars no longer need to write about his critical neglect; the critical ground has been cleared, and it should make way for criticism that pays more attention to Baldwin’s style—to his formal qualities as poet, playwright, novelist and essay writer. I think, too, that critics will turn to his less well-known work—his speeches, interviews and short stories, as well as his poetry and critically neglected novels (Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone).

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.