Remembering Marcus Garvey Through Reggae

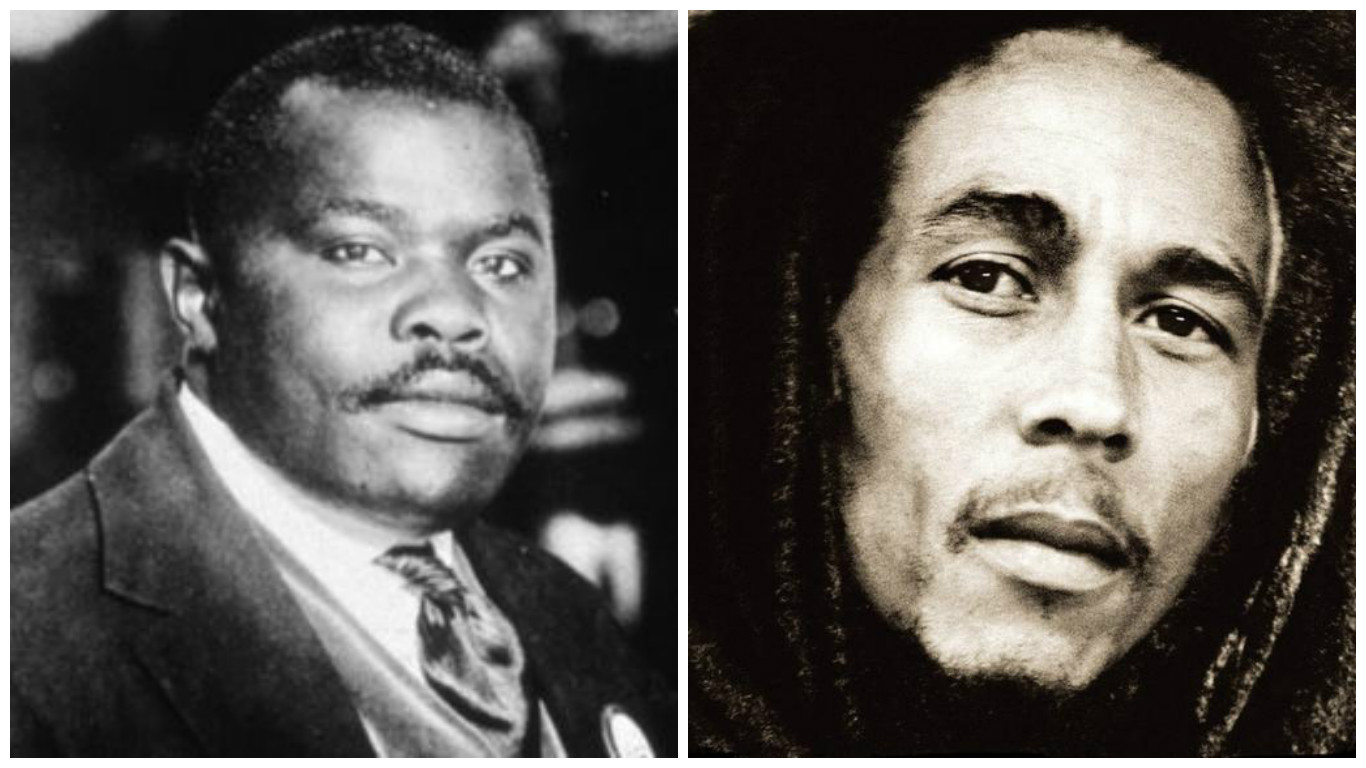

Listen to the music. February 6 marks the birthday of Bob Marley. Born in Jamaica in 1945, the Reggae icon would be witnessing his seventy-second birthday if he were alive today. Over the next month or so, Marley fans will be celebrating the music and life of this legend. While not a man without fault, the “Tuff Gong” used his music as a tool of anti-colonialism. Marley was a cultural ambassador for Rastafari, black liberation, and pan-Africanism. His poetic lyrics set a troubled world on fire, defended black self-determination, and urged the African world to unite. It is thus of little surprise that Marley was subject to state-sponsored violence. Marley’s birthday week is an opportune time to revisit not only his legacy, but the black radical tradition as told through reggae. Marley was heavily influenced by the life and lessons of Marcus Mosiah Garvey. Scholars like Rupert Lewis have demonstrated how, in addition to Haile Selassie, Marley’s music featured quotes from Garvey. Take, for example, the popular phrase from Marley’s “Redemption Song,” “Emancipate yourself from mental slavery, none but ourselves can free our minds.” That phrase was a taken from a 1937 Garvey speech.

In recent years, scholarship on Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) has received increased academic visibility. The growing popularity around “Garvey Studies” is reflected by last year’s Global Garveyism symposium at Virginia Commonwealth University. AAIHS has tremendously featured emerging studies on the UNIA, particularly in the critical areas of gender, the movement’s global scope and personalities, and its influence on black internationalism. My own work has explored Garvey’s life and influence, including a master’s thesis on the UNIA in Bermuda, which I wrote in 2000.

Those were interesting times to write about Garvey. During my matriculation through Howard University’s PhD program in African Diaspora Studies, I wrote a brief paper about Ida B. Wells for a History course. In doing so, I passingly mentioned how she was to represent the UNIA at the 1918 Versailles Peace Conference in Paris (until the US Government prevented her and A. Philip Randolph from traveling abroad to do so). I found the professor’s handwritten note next to that line to be curious—“Only at Howard University is this important!” Written next to a smiley face, it was ostensibly meant to be a joke. I graciously took the “A” but also took issue with the comment. Why? Because I had been introduced to Garvey like I believed that most black people across the world had been–through lived experiences outside of the academy. In my opinion, Garvey was mainstream, and I viewed those the comment as an assault on a whole universe of black consciousness. In the long term this was a small matter. But this brings us to a more critical point—the unveiling of the UNIA’s broader narratives brings greater visibility to marginalized historical figures. It also asks us to think about the numbers of scholars and graduate students who found themselves marginalized, denied research funds, left off of bibliographies, forced to change dissertation topics, or railroaded for exploring topics in ways not yet legitimized by their advisors, professors, and academia at large.

Thankfully, that random comment on my paper was not representative of my overall experience at Howard. I was blessed to have studied Garvey with Howard Professor Emory Tolbert, whose pioneering work on the UNIA in California speaks for itself. Books like Ula Taylor’s Veiled Garvey (2002) legitimized these graduate projects for many of us. And while it is somewhat easy to celebrate pioneers, we do not always recognize the struggles that it takes to be a trailblazer. Scholars like Tolbert and Taylor blazed a trail for me and so many other scholars. Outside of the academy, reggae has been one of the primary mediums through which black communities learned about Marcus Garvey. Even when Garvey may have been relatively invisible in the hallways of academia, he was amplified in the dancehalls, stage shows, and sound clashes. Excellent historiographies allow us to read Garvey. Below I offer a sample discography—or a cultural finding aid, if you will—to enable us to listen to Garvey through reggae.

Late 1970s

In the late 1970s, I would argue that reggae was the most prominent musical voice of pan-Africanism and African liberation. In this era, it’s hard to find a reggae album that doesn’t reference Garvey. Many of the albums below are replete with references to Garvey, Steven Biko, South Africa, Toussaint L’Ouverture and the Haitian Revolution, Black Panther George Jackson, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, lynching, black urban revolutions in London, and Jamaica’s Paul Bogle.

- Burning Spear’s Marcus Garvey (1975)

- Peter Tosh’s Equal Rights (1977)

- Steel Pulse’s Handsworth Revolution (1979), Tribute to the Martyrs (1979)

- Culture, Two Sevens Clash (1976).

1980s

By the late 1980s Reggae would go through dramatic changes in technology, style of singing and chatting, and sound. But as the geo-politics of the world changed (the nuclear arms race and the intensifying anti-apartheid movement, for example), Reggae’s content and scope did so as well (enter Lucky Dube and Samba Reggae). Still, it maintained a strong consciousness of racial and world issues. The songs included in the albums below speak of global power struggles in placed like Cuba, Libya, Uganda, Ethiopia, South Africa, and Nicaragua.

- Bermuda’s Ital Foundation (1980), Ital Foundation Vol 1

- Steel Pulse, True Democracy (1982)

- Rita Marley, Who Feels It Knows It (1982)

- Super Cat’s “Under Pressure” on the Heavenless Riddim (1984)

1990s

Driven through the era of sound and artist clashes (Shabba Ranks vs. Ninja Man vs. Super Cat, Bounty Killer vs. Beenie Man), by the 1990s dancehall had come into its own. Even while “slackness” lyrics of violence and misogyny marked the dancehall, the consciousness of Africa in the music did not disappear. In the mid-nineties, Reggae went through a cultural renaissance, calling for more of its traditional themes. Artists such as Tony Rebel, Garnett Silk, and Luciano led the way.

- Capleton, Prophecy (1995)

- Buju Banton, Til Shiloh (1995)

- Sizzla Kalonji, Praise Ye Jah (1997)

- Mos Def & Talib Kweli, Are Black Star (1998)

- Lauryn Hill, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill (1998)

2000s

What Sizzla started in the 1990s, he continued throughout the next decade. His 2002 album Da Real Thing (its on my top ten Reggae albums of all time list) reflected how the political consciousness of emerging Reggae artists such as Tarrus Riley, Richie Spice, Queen Ifrica and Gyptian remained relative to a Dancehall and “Lover’s Rock” audience. This phenomenon was also driven by a number of Reggae and Dancehall artists who produced songs over the same beats, such as the Diwali riddim (created in 1998 but released by Greensleeves in 2002), Don Corleon’s Drop Leaf riddim (2004), the Blackboard riddim (2007) and the Nyabinghi riddim (2010). This included the likes of Assassin (Idiot Thing That), Mavado (On the Rock), Konshens (Rasta Imposter) and Jah Cure and Fantan Mojah, “Nuh Build Great Man.”

- Morgan Heritage, “Black Man’s Paradise” (2000)

- Dead Prez, Let’s Get Free (2000)

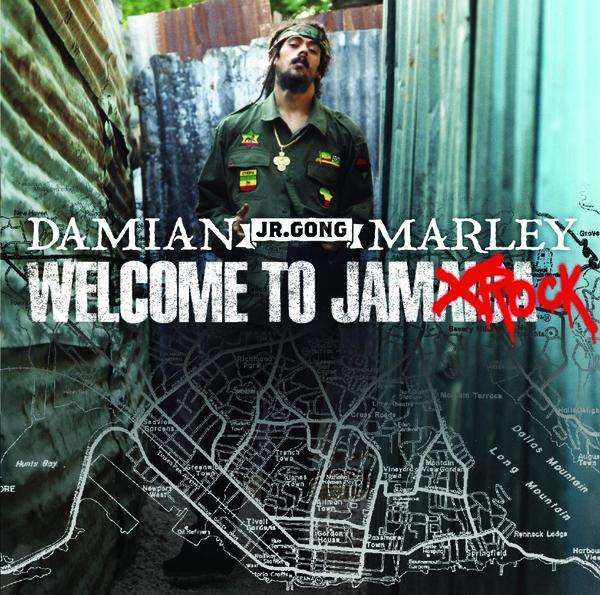

- Damian Marley, Welcome to Jamrock (2005). *Intro track “Confrontation” features the voice of Garvey through a sample of one of his speeches.

- Queen Ifrica, Fyah Muma (2006) and Montego Bay (2009)

- Etana, The Strong One (2008).

2010s

Over the past decade, Reggae artists such as Chronixx have helped to continue Rasta’s critique of Babylon, white supremacy and the oppression of Black people. I often use Chronixx’s music in my own classes on Music and Protest in the African Diaspora. Reggae has continued to call for repatriation to Africa, social justice, the legalization of marijuana, even as Caribbean governments continue to pay lip service to the decriminalization of the plant. Amidst the lyrically explosive dancehall clashes, fans, listeners and scholars of Reggae continued to be inspired by songs such as Mavado’s “The Truth,” Vybz Kartel’s “Unstoppable,” and Popcaan’s “System.”

- Damian Marley and Nas, Distant Relatives (2010)

- Protoje, “The 8 Year Affair” (2013)

- Chronixx and Zinc Fence Massive, Dread and Terrible (2014)

- The Marcus Garvey Riddim (2015)

Thank you for this wonderful piece. This is the music I grew up on. I wanted to add that in addition to the misogyny and homophobia (which unites some of the more conscious and slack artists alike), there is also a strong strain of women’s empowerment: (Judy Mowatt), critique of masculism (Queen Ifrica, Times Like These), and a bold advocacy of women’s sexual freedom (Lady Saw, What is Slackness). These exist alongside the critique of Babylon and empire in a sometimes contradictory mashup that perhaps speaks to power struggles of a different (but not unrelated) kind.