Race and Imperialism in Canada in the 1960s

In recent years, scholars and activists in Canada have been drawing more attention to the country’s often-unacknowledged history of slavery. The Montreal Gazette recently interviewed historian Dorothy Williams and rapper/educator Aly “Webster” Ndiaye about the history of slavery in Quebec. Speaking on CTV News, Afua Cooper, chair of the Black Studies department at Dalhousie University, argued that a historiographical focus on the Underground Railroad had the effect of pushing Canada’s history as a slave-holding nation “under the carpet,” when, in fact, “for two hundred years … the dominant condition of Blacks in this country was one of enslavement.” Slavery, of course, is but one element of a larger pattern of imperialist practice. In another recent piece, McGill University professor Charmaine Nelson argued that contemporary Canadian racism cannot be understood “without an understanding and acknowledgement of its historical, colonial roots.” Nelson sees contemporary racism in Canada as “a continuation and adaptation in another form,” of “infrastructures of racist oppression which were put in place centuries ago to differentiate free from unfree people” in Canada.

If it is a struggle to get white Canadians to understand their country’s history of enslaving and oppressing African and Indigenous people at home, it may be even more difficult to get them to see how racism and imperialism have shaped Canadian perceptions of, and interactions with, the developing world. Yet, as Todd Gordon has pointed out, Canada is a nation that “actively participates in the global system of domination in which the wealth and resources of the Third World are systematically plundered by capital of the Global North.” One relatively recent example of Canada exercising power in the developing world in order to shape local conditions for its own benefit is its involvement in Haiti during and after the downfall of the Aristide government, which activists/journalists Yves Engler and Anthony Felton call part of a plan to transform Haiti into a place that was “good for business–our business.” This, as 94% of Canadians see their country as a “force for good in the world.”

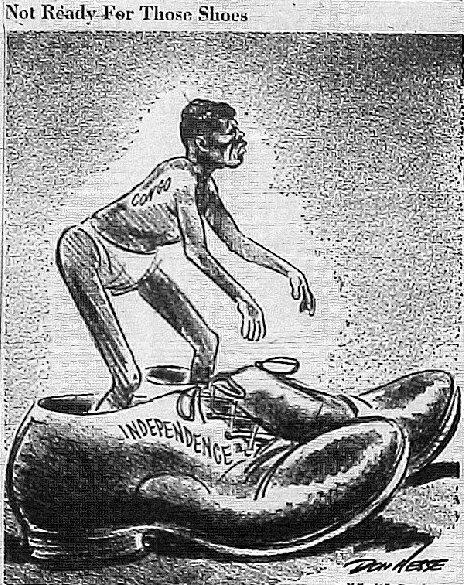

portrayal of the Congolese people, 15 July 1960

It was through my study of the closely-intertwined West Indian and Canadian iterations of Black Power that I began to rethink the prevailing image of Canada as a force for international good. In the 1960s, Black intellectuals in Canada and the Caribbean strongly criticized Canadian neoimperialism in the Caribbean, using historical and social-science analyses to address issues including the extractive activities of Canadian bauxite-mining operations, Canada’s major role in West Indian banking undermining economic sovereignty, the negative economic and social effects of Canadian tourism, and Canadian military activity in the region. That analysis unfolding within the intellectual context of Black Power could force a re-evaluation of Canada’s overseas activities should come as no surprise; Black Power was an inherently anti-imperialist movement in which the oppression of the African diaspora was understood as part of a larger imperialist system of uneven power relationships between core and periphery, expressing itself in Vietnam as much as in Detroit, Brixton, Bridgetown, or Montreal.

During the 1960s as West Indian nations were becoming independent and anti-colonial struggles in African nations like Congo, South Africa, and Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia) were intensifying, everyday public discourse in Canada worked to frame the West Indies and Africa as objects of imperial control. In a previous post, I wrote about how the Congo crisis and the murder of Patrice Lumumba generated profoundly imperialist reactions from the Montreal press. Commentators blamed unrest in Congo on a Belgian failure to prepare their African wards for independence and on the fact that Africans had “no relevant history” to act as a basis for a nation, and portrayed Africans as violent brutes.

These themes were common in Canadian public debate about anti-imperial struggles in Africa in the 1960s. While many Canadians expressed horror and outrage at prominent instances of settler colonial brutality such as the 1960 Sharpeville massacre, professional commentators and readers of the daily press consistently discussed African resistance to imperialism in terms that reproduced imperialist ideas about Africans as inherently uncivilized and violent. Sometimes these tendencies could co-exist in the same text, such as in 1960, when Montreal Star editor George Ferguson attacked apartheid while noting that African nations lacked the “tradition and maturity” to follow Canada’s lead as an independent member of the Commonwealth. 1 Imperialist discourses about Africa in the Canadian press were amplified by the participation in public debate by people from white settler communities in countries like South Africa and Rhodesia, who wrote to Canadian papers from Africa, while travelling in Canada, or in the case of some people, after having settled in Canada after leaving Africa out of fear of the impending end of white minority rule. People from minority white regimes in Africa wrote to the daily press to criticize the Canadian media for failing to draw sufficient attention to how “Negro mobs” were engaging in violent acts against white settler communities that were “fighting for survival” even as they had “done some splendid work to uplift the Negro.” 2

Many of the imperialist themes that emerged in Canadian conversations about Africa also appeared in Canadian public debate about the English-speaking Caribbean as Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, and Guyana became independent. Discussions about the West Indies, however, were often framed by a tone of paternalism informed by the assertion that as the senior member of the Commonwealth in the Americas, Canada had a special obligation to help their junior Commonwealth partners as Britain loosened its hold on the region. Looking south, Canadians had to use aid and trade as ways to “claim the stake which was naturally [theirs].” 3

Crucially, Canada’s reputation as a friend to the poorer nations provided a justification for the exercise of imperial power in the Caribbean. As Nova Scotia politician Gerald Regan put it, Canada’s apparent reluctance to be seen as a colonial power made Canadian aid “less suspect and more palatable” than American aid. At the same time, Regan proposed that West Indian national currencies be replaced by the Canadian dollar — a move that would totally undermine regional economic sovereignty. 4 Even as Canadian politicians, pundits and newspaper readers urged Canada to do more in the West Indies, they spoke about the region in terms of its alleged backwardness and its potential to threaten hemispheric political stability: the press called the Jamaican people an “unsophisticated electorate” who could be “swayed by demagogy,” and portrayed some regional leaders, notably Guyana’s Cheddi Jagan, as having the inclination and the potential to launch Cuban-inspired violent revolutions in the West Indies.5 As in the case of Africa, Canadian discourses about the West Indies reflected deeply imperialist attitudes.

The discourses I’ve described here form part of the background against which Canadian and West Indian intellectuals and activists, working under the banner of Black Power, formulated their critiques of Canadian racism and imperialism. Writing in 1966, Alfie Roberts, a key figure in the development of West Indian and Black Canadian radical thought, described Canadian attitudes towards the West Indies as a mix of “sympathy, paternalism and bossism.” 6 Analyses of Canada’s racism were informed in large part by the everyday struggles of Black people in Canada, where employment and housing were key sites of systematic anti-Black racism. Critically, they were also informed by the racism and imperialism experienced by West Indians at the hands of Canadians back in the Caribbean, be it in terms of the Canadian banks and corporations that controlled huge parts of West Indian economies or from Canadian tourists who brought their racism with them to the islands. When the Black Power revolution broke out in Trinidad in February 1970, it began with a march on the Canadian High Commission and the head office of the Royal Bank of Canada in Port of Spain, revealing the extent to which Canada was seen as part of the problems facing marginalized West Indians.

Like its history of slavery and structural racism, Canada’s history neo-imperialist ideas about, and relations with, the developing world remain largely unacknowledged in the national narrative; studying the critiques of the people who experienced Canadian racism and imperialism first-hand should be a key part of Canadian historiography and history curriculum if the country is to begin to come to terms with important, and still too-often overlooked, dimensions of its past.

- “Racial Issues Destroy Close-Knit Association,” Montreal Star, October 19, 1960. ↩

- Jonathan Anderson, Montreal Gazette, April 13, 1960; Archibald Harshaw, Montreal Star, November 21, 1961; Archibald Harshaw, Montreal Star, September 30, 1963. ↩

- Robert C. Hanson, “Canada’s Caribbean Role,” Montreal Star, February 15, 1968. ↩

- “Canada Should Help Caribbean,” Montreal Star, April 26, 1968. ↩

- Raymond Sharpe, “Jamaica Sees Violence,” Montreal Star, October 8, 1966 ↩

- Alfie Roberts, “Why We Must Think for Ourselves,” Flambeau, November 1966, 1–7. On Roberts, see Alfie Roberts, A View for Freedom: Alfie Roberts Speaks on the Caribbean, Cricket, Montreal, and C.L.R. James, ed. David Austin. Montreal: Alfie Roberts Institute, 2005. ↩

hi id like to know the cause and effect of this. id also like to know the who what why when where and the how. thank u 🙂