Marable’s Malcolm: A Revisitation

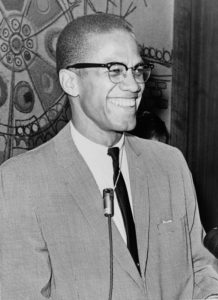

Writing about Malcolm X can feel like stepping into a whirlpool. The further one ventures beneath the currents, the more one is drawn into a vortex of pain. Born May 19, 1925, Malcolm died February 21, 1965, in a fusillade of bullets, while articulating the realities of those on the margins of society. Sooner or later, many who attempt to chronicle his life conclude that the man was doomed to embody the suffering of the most vulnerable segments of black America. Indeed, few Malcolm biographers escape the curse that afflicted their subject: the burden of bearing the trauma of generations of oppression.

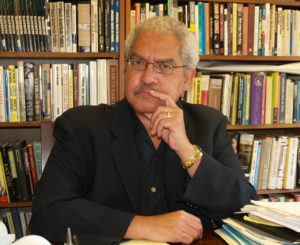

If anyone seemed capable of carrying the psychic weight of Malcolm’s life, it was my late mentor Manning Marable. Marable was a prominent historian and the founding director of Columbia University’s Institute for Research in African American Studies (IRAAS). When I met him in 2002 he had been seriously investigating Malcolm for almost 15 years. A perceptive interpreter of black freedom struggles, Marable appeared to be the ideal candidate to craft the authoritative political biography of Malcolm. What he produced in the end was rather more complicated. Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, the professor’s Pulitzer Prize-winning tome, is as insightful as it is fraught and uneven. 1 Marable’s untimely death on April 1, 2011, days before the release of the long-anticipated biography, added a dimension of heartbreak. The tragedy that surrounds Malcolm’s memory seemed to have engulfed one of his most gifted interlocutors.

There was a time, however, when Marable’s exploration of Malcolm was a source of unbridled excitement for the scholar and for many of those around him. I joined the Malcolm X Project (MXP), an IRAAS initiative led by Marable, during my first year in grad school. The Project brought together students and budding scholars who were tasked with contextualizing the late leader’s autobiography, conducting oral histories with his close associates, and producing chronologies and other resources to enhance the collective study of his life and times. At the center of the MXP’s intellectual vibrancy was Marable himself, an enthusiast who saw the study of Malcolm as an essential link between IRAAS and the people, cultures, and destiny of neighboring Harlem.

Marable’s admiration for Malcolm as an exponent of the Black Radical Tradition undergirded the work of the MXP. But late in my graduate career, as Marable drafted early chapters of his biography and shared them with some of his students, a growing concern began to temper my passion for the Project. I started to notice a gap between the tenor of Marable’s prose and the great affection for Malcolm that the scholar expressed in person and in his teaching and labors as a public intellectual.

This discrepancy led to the only brief clash that Marable and I ever had. After reading a section of the professor’s manuscript in progress, including a passage recounting Malcolm’s derision of the 1963 March on Washington, I raised several objections. In a meeting with Marable, I questioned his depiction of Malcolm as a bitter detractor fuming in the shadows of the demonstration. I argued that despite the symbolic appeal of the event and the extraordinary mobilization behind it, the march had largely functioned as Malcolm predicted it would—as a pageant that validated the Kennedy Administration’s pending civil rights bill while silencing or deflecting more militant tendencies within the movement. To downplay such tendencies, I contended, was to mask the legitimate fury that erupted in Harlem in 1964 and throughout the “long hot summers” that followed. As I saw it, Marable’s chapters dismissed the politics of insurgent dissent while reifying liberal integrationism as the defining framework of black liberation. Marable, however, disagreed with my appraisal, and we discussed the matter no further.

When the Malcolm biography was released a few years later, questions immediately arose about the validity of its historical interpretations, spawning intense public debate within the field of black studies. The 2011 book received accolades from many prominent journals and intellectuals. Yet a number of scholar-activists openly criticized Marable’s conclusions. Several of the most scathing black nationalist and left-of-center critiques were anthologized in a polemical volume titled A Lie of Reinvention: Correcting Manning Marable’s Malcolm X. 2 The charges therein echoed in strident fashion those that critics had leveled elsewhere. According to these detractors, Marable had endeavored to belittle and distort Malcolm and to neutralize him as a radical icon. He had trafficked in speculation and salacious innuendo; failed to adequately cite or acknowledge the work of previous Malcolm historians; and served the counterrevolutionary agenda of the ruling class (as dictated by Viking Press, the biography’s publisher) by recasting Malcolm as a liberal Democrat, a rebranding for the “post-racial” Age of Obama.

To be fair, some objections to Marable’s text were based on careful analysis. Historian Sundiata Cha-Jua, for example, argued that the biography’s theme of “reinvention” constituted a cynical reframing of what countless observers had simply characterized as Malcolm’s political evolution. Other critiques were less principled. Many of the harshest condemnations depicted Marable as an “elite” Ivy League academic far removed from the sensibilities of Malcolm’s grassroots constituency, a notion that seemed to ignore the entire corpus of the scholar’s political life and work. The problem, of course, was that Marable was unable to face his accusers, whatever the merits of their claims. And his conspicuous absence encouraged the ad hominem nature of the attacks.

Marable would have relished the intellectual jousting that followed the publication of his final work. (One of his advisees, Zaheer Ali, served as a capable proxy, contextualizing the biography in many interviews and debates.) In the aftermath of Marable’s death, however, many of his former students were too grief-stricken to sift through multiple critiques of the book, and too dismayed by baseless or virulent denunciations to formulate cogent responses. Indeed, the wrangling over A Life of Reinvention deepened the pain that many Marable protégées felt in the wake of the intellectual’s passing. Shaken by the recrimination, and unprepared to face the implications of the interpretive lapses that I had detected in the text years earlier, I shelved my copy of the biography. Occasionally I perused a chapter or two, but I could not bring myself to teach or substantively engage the work.

Then April 1, 2016 arrived—the fifth anniversary of Marable’s death. I decided that the time had come to revisit A Life of Reinvention. I knew the study was not Marable’s magnum opus. (That distinction belongs either to Race, Reform, and Rebellion or to How Capitalism Underdeveloped Black America.) 3 Yet as I started rereading I was struck by the biography’s strengths. Its treatment of Malcolm’s last year is particularly illuminating. A Life of Reinvention captures the competing political impulses and trajectories of those final months. Marable depicts Malcolm’s torturous escape from the dogmas of the Nation of Islam, his search for a coherent ideological framework, and his efforts to rebuild an organizational base.

The leader’s political and rhetorical contradictions in this period of rapid development are vividly revealed. We find Malcolm seeking greater influence within the centers of African-American struggle while continuing to castigate King and other figures, preaching all-black unity while honing the language of class revolt, and tacking toward then away from Third World models of socialism. We also learn new details about the political dynamics of Malcolm’s treks through the postcolonial world, from Ghana to Nigeria to Algeria to Egypt. And we get a fuller picture of his campaign to charge the United States with human rights abuses before the UN.

Yet the disparaging tone of Marable’s prose remains a distracting and at times infuriating element of the text. Malcolm is cast as a provocateur given to bluster and excess, rather than as a radical who skewered the duplicity of the American narrative of racial progress and democratic inclusion. Marable alternates between condemning Malcolm’s “stridency” and portraying him as an aspiring civil rights leader who was coming to terms with the creed of “multicultural universalism.” The depiction of integrationism and liberal reform as normative models of social change is the most disappointing aspect of A Life of Reinvention.

Nevertheless, Marable’s book will prove useful to those who wish to understand Malcolm’s later political metamorphoses, particularly his attempts to transcend the theoretical boundaries of racial thought and embrace more expansive principles of anti-imperialism and anti-capitalism. Though Malcolm’s final year is endlessly fascinating, one must resist the temptation to draw sweeping conclusions based on the leader’s last pronouncements and deeds. Malcolm, like Marable, was not preparing his final testament, only struggling imperfectly toward a vision of freedom.

- Manning Marable, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention (New York: Viking, 2011). ↩

- Jared A. Ball and Todd Steven Burroughs, eds., A Lie of Reinvention: Correcting Manning Marable’s Malcolm X (Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 2012). ↩

- Manning Marable, Race, Reform, and Rebellion: The Second Reconstruction in Black America (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1984); Manning Marable, How Capitalism Underdeveloped Black America: Problems in Race, Political Economy, and Society (Cambridge, Mass.: South End Press, 1983). ↩

Malcolm X was a part of my teenage years and I always found him, and other black revolutionaries, fascinating and still. I have always thought that his association with the NOI really constrained Malcolm X and it’s until later that he became a true revolutionary.

Professor Marable’s “Malcolm X: A Life Of Reinvention” was interesting and well researched, but it did not bring fresh interpretive light on the significance of Malcolm X in the development of late 20th Century African American life and culture. Marable hews close to the now conventional picture of Malcolm as a thoughtful leader who blossomed upon his emancipation from the conservative and corrupt Nation of Islam. In so doing, Marable missed the opportunity to investigate the Nation of Islam itself as a movement of reinvention. In accepting the plot of Malcolm as the active agent and Elijah Muhammad’s organization as a limiting structure, Marable has missed Malcolm’s larger engagement with the major indigenous American Islamic movement. On page 470, Marable briefly mentions the renaming of Harlem Mosque Number 7 as Masjid Malcolm Shabazz. Marable treats this as epilogue, failing to question how Wallace Mohammed, Malcolm’s erstwhile ally and Islamic mentor, could achieve a complete redirection of the Nation of Islam a scant 12 years after both he and Malcolm had been excommunicated.

We still await a scholar who will begin to evaluate Malcolm X’s larger contribution as an architect of a new African American consciousness that includes Islamic knowledge in its critique of white supremacy.

Thank you for this thoughtful and no less critical reappraisal of your mentor’s final book. Like Qasim Abdul-Tawwab, I did not find the book to be particularly more illuminating than the existing scholarship on Malcolm. Marable’s prose were characteristically beautiful and the plot lines of his life were most certainly thickened, however, the book failed to transform the sub-field of Malcolm X Studies and point us in a new direction. But I agree that the book can have value in the classroom and provide some greater details and insights into the final years of Malcolm’s life.

Agreed, Fanon! Many thanks.

Thank you for writing this. The aftermath of the publication of Manning Marable’s book was an intellectual turning point for me. I agree about the comments about Marable’s assessment of the NOI, especially as I have found the NOI newspaper Muhammad Speaks to operate in ways that furthered radical internationalism and African consciousness. There is much work to be done on the NOI’s role in Black life and the story is more nuanced than portrayed. Notable in the book’s earlier chapters are the various afterlives of the Garvey movement in Black life. Garvey scholarship is now thriving and my initial read of this book was an apt reminder of these intellectual influences. One of the freshest things I’ve read on Malcolm is the article by Komozi Woodard and Erik McDuffie on the radical women that influenced Malcolm and I recommend it to all: http://www.slideshare.net/ErikMcDuffie/erik-s-mcduffie-and-komozi-woodard-if-youre-in-a-country-that-is-progressive-biography-36-3-summer-2013-507539-54982977

Thanks, Robyn! I agree that some of the best and most exciting work being done on Malcolm involves his relationship to radical women. We continue…

The book MALCOLM X: LIES OF REINVENTION is a “must” critical companion for Marable’s book. Available from Black Classic Press, a solid critique from multiple authors, including Amiri Baraka, which rightly charges, among many other things, that Black Radical Tradition is subverted, ignored and betrayed in Marable’s book.

Although I read and absorbed the book cover to cover, at times my jaw dropped at his scolding characterizations/caricatures “shoplifters, criminals” and the like when discussing Malcolm himself, friends and family members. Really? And the weird handling of Malcolm sexuality bits —also very “tone-deaf”and inappropriate frankly. How is it anyone’s business? This was a complex, soulful man. I ain’t mad at NUTHIN’ except prudish conjecture ABOUT him.

Although I appreciated Marable’s work for its more in-depth look at Malcolm’s life, it’s the “LIES” book I keep on my shelf, not Marable’s.

Prof. Rickford, this is excellent. I teach “A Life” and “A Lie” side by side and it takes my class about two hours of discussion to arrive at the incisive points you so thoroughly elucidate here. Sadly, so much of the mainstream work on Black Power seems domesticated in favor of liberalism these days, so much so, that your new book stands out as a welcome exception. Congrats on that as well. Upon reading “We Are an African People,” I remained unfailingly impressed by your materialist critique and your encyclopedic knowledge of black nationalist movements, both in and beyond the field of education. I also became increasingly curious about where you might come down on Marable’s final work. Now I know. There’s a troubling parable, perhaps, in the trajectory of Marable’s scholarship, his relationship to liberalism, the possible pursuit of wealth and renown. Only those closest to him can know for sure. Still, we historians can only hope to have done as much good as Prof. Marable did in life. Again, thanks for your manifold efforts.

post to my website (where the hyperlinks appear):

Last month Russell Rickford published this commemoration of his late mentor Manning Marable. In it Rickford makes mention of our anthology which criticizes the final work attributed to Marable, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. i understand that Rickford’s is more of a short essay and is part of a wider reflection of that journal on the life and work of Marable and that it is not a focused critique of our work (a point to which i will return). But this is precisely why our work came to be; to help fill a tremendous void created by the massive product that became the final work attributed to Marable and its almost unquestioned welcoming by not only the establishment from which it was produced but so many activists, academics, journalists and lay readers alike. It was the force of Marable’s well-established (and deserved) brand that propelled then and now a defense of the final work carrying his name that i continue to think exists mostly (only) to distort Malcolm X as a symbol himself of ideas which still inspire fear among those who claim now to know best how to present him/them to us.

What i see in Rickford’s essay is a re-presentation of so much of what we were challenging. As i attempted to clarify with him via email, Rickford repeated a common approach, as many defenders of the final work attributed to Marable were/are prone to do, most notably, the use of references to critics as straw arguments to defend their friend, mentor or ideological compatriot. There is no real interest or attempt in truly engaging a criticism which for defenders only exists to validate their ally.

As for Rickford’s passing reference to and deployment of our work in his essay, the ignored or unmentioned substance, reasoning, research or logic of my colleagues’ work and they can speak for themselves. For me and my unmentioned argument against the final work on Malcolm X attributed to Marable, it has always been the same and based on what i argue is the book’s political function to distort, diminish and discourage the updated implementation of the radical ideas with which Malcolm was most grappling at the end of his life; pan-Africanism, nationalism, socialism, anti-imperialism/colonialism, anti-capitalism, anti-White supremacy and armed struggle. i feel that the final book attributed to Marable is a departure from Marable’s own previous work on Malcolm X and the Black Radical Tradition more broadly speaking and that it should be critiqued as a state/corporate attempt to re-brand Malcolm X, a man and symbol that looms too large for full erasure, as one more palatable to White capital (even beyond what is in my introduction is what i’ve said here about this last point). And while i offer several detailed and cited examples as to why i reached those conclusions nowhere have i seen, certainly not in Rickford’s essay, any specific reference to my argument, its logic or quality of scholarship. What i have seen time and again are essays like Rickford’s that will use diminishing language to describe my conclusions but nothing about how they were reached.

It is precisely this inattention to the specifics of the political and ideological arguments made by me and my co-authors that most exposes their value. It is the suppression, even in what should/could be reasonable debate among those readers of the final book attributed to Marable, of even discussion of revolutionary ideas that suggests our criques of the book attributed to Marable regarding that book’s approach to those politics that most fully demonstrates the political, intellectual and organizational emptiness among so many of us who claim to value Malcolm X or even the career of Manning Marable.

Therefore, being offered no space in the journal to respond to Rickford and our email exchange being just that, here are just a few points of response i’d like to offer:

Our book is only mentioned really to play the roll of a kind of straw antithesis to Marable as the sound, reasonable, true people’s scholar (which he largely was and why his final book should be seen as the departure i/we claim it to be and then critiqued as such). So there is no substantive engagement with our arguments, no references to specific statements to either confirm or deny their veracity. Only one of our contributors is mentioned by name as worthy of some praise and even then there is no detail as to why his is the only valuable contribution.

Not one word is said specifically detailing, citing or referencing any of the critiques in our book of the final work on Malcolm X attributed to Marable that Rickford dismisses with skillful use of words/phrases like “polemical” and “ad hominem.”

The straw nature of our presence is furthered by Rickford in his revival of what comes across as disingenuous lamentations over Marable’s inability to face his detractors considering Malcolm could not face his and worse that few (none?) of the defenders of the final book on Malcolm attributed to Marable demonstrate a willingness to debate principled critics of the product (a point which we have made repeatedly for some time now). For example, Rickford goes so far as to claim that Marable’s former lead researcher Zaheer Ali has appeared in multiple “debates” and with prowess defended the merits of the book. But as i pointed out to Rickford, not only is this entirely false but the closest to debate Ali has come was one with us where he was not alerted by an Al-Jazeera producer that we would be there (and to be clear, we did not know this was the case either). Ali refused invitation to my then radio show where i invited him and the entire Marable research staff to appear to answer questions i would furnish weeks in advance. Actually, it may be that he has canceled more debates than he has taken up since at least twice he canceled planned appearances to university debates upon hearing i would be there, once at Ithaca College and another at The University of Maryland at College Park. This would be fine if he had debated anyone else. It has never had to be me. i am unaware of any debate on this book in which Ali has engaged with anyone, anywhere, at any time and i made that point clear in my emails to Rickford. In fact, i asked Rickford more than once during our exchange of emails to cite even one example of the “debates” he says Ali took up. He offered none. My point here is that while claims are repeatedly made about Marable’s inability to defend himself (a point we lament as well) and how he would have treasured the opportunity to engage his critics, it is his defenders who routinely stifle sound debate.

Finally, and again, for me the argument here is mostly about the radical ideas with which Malcolm worked and that i still think need more attention, infusion and implementation today. i think the final book on Malcolm X attributed to Manning Marable assaults these ideas and does more to contort Malcolm X into a figure who would have somehow found reconciliation with the world today and its leadership – a point i made specifically about the book’s epilogue. i think intellectual products like the final book on Malcolm attributed to Marable are an integral part of attempts to prevent us and successive generations from taking up revolutionary concepts and to the extent successful we are weakened going forward. We are not served well by those who deny debate under the guise of individual praise or reverence for scholarship.