“Liberated Territories” and Black Radical Praxis

Always bear in mind that the people are not fighting for ideas, for the things in anyone’s head. They are fighting to win material benefits, to live better and in peace, to see their lives go forward, to guarantee the future of their children. –Amilcar Cabral, West African revolutionary1

In a recent article for the Nation, journalist Juan Cole likened the crisis of contaminated water in Flint, Michigan—a largely black and poor city—to some of the daily crises of powerlessness endured by the Palestinian people. Cole argued that both populations had been deprived of basic autonomy, and that both were experiencing a form of colonialism.

One of the most striking aspects of the essay was the author’s use of the colonial analogy, the once-familiar claim that marginalized African-American communities constitute colonial possessions of the U.S. During the Black Power era of the late 1960s and 1970s, the “internal colony” theory was a central organizing principle for an assortment of black nationalists, Pan Africanists, and leftists, from organizers of the Revolutionary Action Movement to members of the Black Panther Party. The formulation helped mark the age of independence, a time when anticolonial struggles in Africa, the Caribbean, and other parts of the Third World culminated in the formation of new nation-states and powerfully shaped the discourses of African-American liberation.

Most contemporary proponents of the colonial analogy viewed “national liberation” as the answer to black America’s political, economic, and cultural subordination. After all, the great wave of post-World War Two revolutions seemed to affirm formal self-government as the essential solution to the dependency of subject peoples. But was nationhood the optimal model of black self-determination? As Wretched of the Earth author Frantz Fanon had once observed, “national consciousness” within African liberation struggles offered both a blessing and a curse, enabling the consolidation of anticolonial forces while bringing to power an elite class of managers committed to governing in its own narrow self-interest.2

During the 1960s and 70s, black American concepts of nationality proved equally contradictory. On one hand the resurgence of nationalist consciousness significantly enhanced the postwar African-American mass movement, raising questions of power and autonomy that had been sidelined amid the push for integration. The reawakening of black nationalism highlighted the strategic limitations of liberal reform and white paternal benevolence. It helped black activists transcend the Cold War framework of “race relations,” enabling them to recognize racism as a system of global conquest and inspiring them to forge new identities and theories of resistance. Paired with Pan Africanism, a dominant tendency of the Black Power movement, black nationalism encouraged dissidents to link the subjugation of African-American communities to larger processes of occupation and underdevelopment.

But the new black nationalism also contained serious flaws. If formal independence had failed to bring genuine freedom and democracy to the masses of the Third World, national sovereignty proved equally problematic as a framework for African-American organizing. Regardless of the color of its progenitors, a nation-state disciplines and regiments its subjects, subordinating to the national mission more organic notions of community and identity. Pan African nationalist institutions in the U.S. (from Afrocentric schools to activist cadres) occasionally mirrored the hierarchies and absolutism of the ruling parties and regimes upon which they were modeled. Attempts to “govern consciousness” and to control African-American working-class behavior replicated the patriarchal, centralized authority of postcolonial states, elevating the prerogatives of the prospective black nation (and its would-be administrators) over the aspirations of the putatively governed. “Most people are not rational, or they are just rational,” intellectual and organizer Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones), declared in 1969, explaining Pan African nationalism’s tendency to regulate the black rank and file. “They function on a less than conscious level. The reason you have to teach people values, values, values is so they will do things that are in their best interest without trying to reason about it.”3

Thankfully, there emerged a more egalitarian framework with which to conceptualize a “postcolonial” African-American future. In the early 1970s, solidarity with armed struggles against the remaining outposts of European colonial rule in Southern Africa increasingly shaped Pan African nationalist politics in the U.S. As black polemicists shifted their attention from independent nations in the developing world to active guerrilla campaigns against white minority rule, the concept of “liberated territories” began to rival the motif of nationhood as a touchstone for African-American political consciousness.

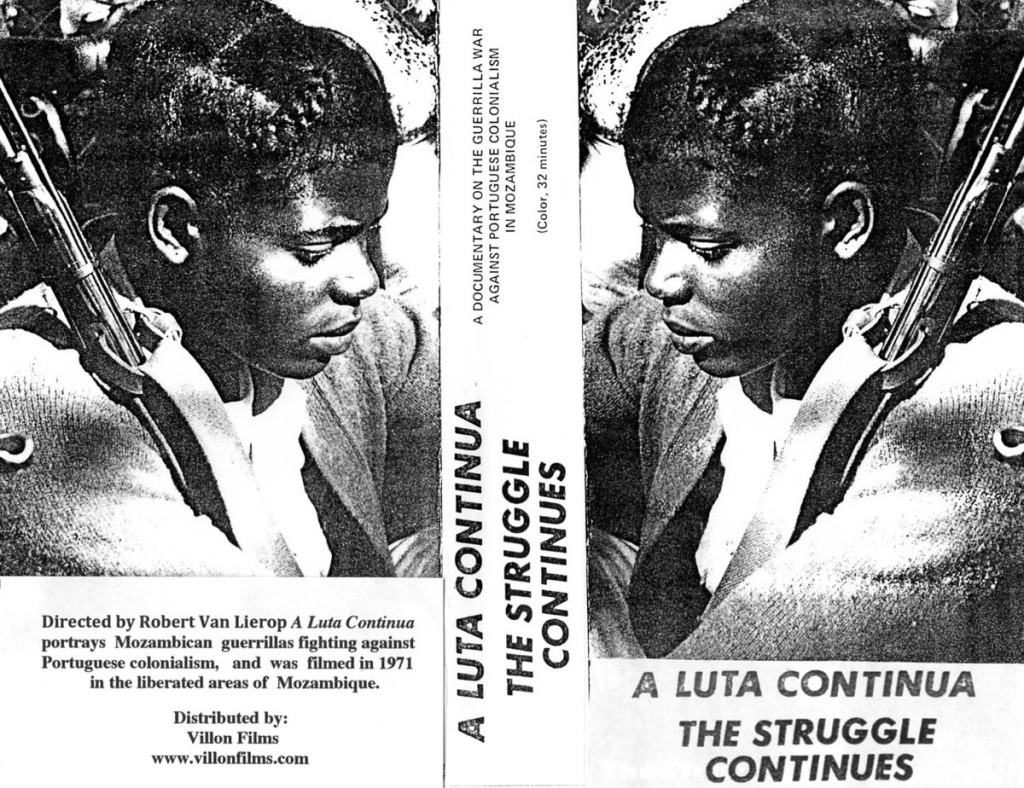

Liberated territories were those rural sites in places like Angola, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Namibia, and Guinea-Bissau that insurgents had wrested from the grasp of colonialists and white settler regimes. Similar zones in South Vietnam and other lands had long captured the imagination of the antiwar activists associated with the multiracial New Left. Recognition of the areas and their significance grew among black internationalists after fall 1971, when key African-American Pan Africanists, including Owusu Sadaukai of North Carolina’s Malcolm X Liberation University and New York City lawyer and civil rights worker Robert Van Lierop, visited liberated portions of Mozambique and spent several weeks embedded with local guerilla forces. This act of solidarity enabled the production of A Luta Continua, Van Lierop’s 1972 documentary film about the Mozambican struggle.

A Luta Continua helped raise African-American awareness about the fight against Portuguese colonialism, as did U.S. visits by Amilcar Cabral (respected leader of Guinea-Bissau’s anticolonial struggle) and the 1972 creation of annual African Liberation Day demonstrations in the U.S. Well-publicized accounts of life inside rebel-held swaths of Southern Africa further established the concept of liberated areas as an important archetype of black self-determination. No longer simply an abstract metaphor, the territories assumed deeper, concrete meaning in many progressive African-American circles.

In published testimonies about his experiences traversing the Mozambican interior with members of that country’s liberation front, Sadaukai explained that the fighters were laboring to emancipate “not just their land but the man on it.” He recalled how the guerrillas had created makeshift schools and hospitals for the benefit of poor villagers, including peasants who had lacked access to basic services under colonialism. Sadaukai described not the workings of a military dictatorship but the efforts of an armed cadre closely integrated with the lives of ordinary civilians and devoted to their dignity and well-being. Screenings of A Luta Continua reinforced this perspective. The film, which traveled the circuits of black consciousness groups in the U.S., depicted Mozambique’s guerrilla forces as a courageous people’s army, a body that viewed revolutionary leadership as a sacred responsibility rather than as a rank or a privilege.4

The political model of liberated territories promised to expand the creative possibilities of black radical praxis in the U.S. Viewing African-American communities not as colonies awaiting national liberation but as potential zones of insurgent democracy required a fundamental theoretical and tactical reorientation. Rather than attempt to forge a disciplined political vanguard (long a preoccupation of leftist cadres), grassroots organizers could immediately begin laying the practical foundations of the new society, as rebel fighters were doing overseas. Rather than imagine a national bureaucracy, black American liberationists could embody the democratic social relations of a radically just community. Rather than instill loyalty to an unborn nation, indigenous black institutions could empower children and young adults to craft a future of their own design. Rather than claim an absolute revolutionary mandate, human rights workers could wage a permanent struggle to win the trust of the people.

For African-American exponents of the liberated zone concept, the reconstruction of power relations was paramount. Leaders would fight alongside the popular masses, taking pains to avoid reproducing the dominant order, and prioritizing the improvement of quotidian life over the ascent to formal self-rule. Gender roles would dissolve, enabling women and men to wield equal authority and perform identical tasks in the struggle. Revolution would be understood not as a bid for power or control but “as a dynamic process of constant change,” the definition advanced in A Luta Continua. Community activists would strive to creatively address the everyday needs of workers and the unemployed. They would do so not to fashion islands of autonomy within a racist empire, but to demonstrate on a modest scale the structural transformation that the whole society needed to undergo.

In the liberated territories of black neighborhoods, the social value of all labor would be honored and rewarded. Decision-making would occur in people’s assemblies. Changes in the status and material realities of the poor and the oppressed would serve as critical measures of revolutionary progress. Socialism would be understood not as an advanced form of statecraft but as acts of self-organization that put oppressed people in command of their lives.

Many grassroots black formations pursued elements of this vision during the 1970s, from liberation schools to urban survival programs to radical feminist groups. If “national liberation” remained a dominant Black Power discourse, an array of political actors within the movement sought more humanistic models of social reconstruction and revolutionary practice. Today, strands of their creative utopianism (an approach not to be confused with political escapism) have resurfaced in autonomous struggles like Black Lives Matter. Young activists are again creating alternative institutions, from communal urban gardens to agricultural cooperatives, designed to prefigure a more humane economy. Many are doing so based on a democratic worldview that explicitly rejects patriarchy, heterosexism, and monopoly capitalism. They are calling for the eradication of white supremacy as well as the basic transformation of social and economic relations, something that neither the postcolonial world nor the post-segregation era has managed to deliver. Armed with their own revolutionary frameworks, they are struggling to reclaim their humanity and build a new society within the shell of the old.

- Amílcar Cabral, Revolution in Guinea: Selected Texts by Amílcar Cabral (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1970), 70. ↩

- Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (New York: Grove Press, 1963). For discussion of the internal colony theory and Black Power internationalism, see Robert L. Allen, Black Awakening in Capitalist America: An Analytic History (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1969); Brenda Gayle Plummer, In Search of Power: African Americans in the Era of Decolonization, 1956-1974 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013); Roderick Bush, The End of White World Supremacy: Black Internationalism and the Problem of the Color Line (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2009); Cynthia A. Young, Soul Power: Culture, Radicalism and the Making of a U.S. Third World Left (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006); Komozi Woodard, A Nation within a Nation: Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) and Black Power Politics (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999). ↩

- David Llorens, “Ameer (LeRoi Jones) Baraka,” Ebony, August 1969, 82. ↩

- Owusu Sadaukai, “Inside Liberated Mozambique,” African World, February 5, 1972; Africa Information Service, “Mozambique: The Struggle Continues,” Black Scholar, October 1973, 44-52; R. Joseph Parott, “A Luta Continua: Radical Filmmaking, Pan-African Liberation and Communal Empowerment,” Race & Class, July-September 2015, 20-31. See also Cedric Johnson, From Revolutionaries to Race Leaders: Black Power and the Making of African American Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007); William Minter, Gail Hovey, and Charles Cobb, Jr. eds., No Easy Victories: African Liberation and American Activists over a Half Century, 1950-2000 (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2007); Russell Rickford, We Are an African People: Independent Education, Black Power, and the Radical Imagination (New York: Oxford, 2016). ↩

This is a really helpful analysis of the approach within black radical organizations in the 70s and into the early 80s. I am writing a biography of a physician named Alan Berkman (1945-2009) whom Mumia Abu Jamal labeled “Brother Doc” when they shared prison time together. Berkman was part of the May 19th Communist Organization, a white anti-imperialist group in solidarity with the BLA and RNA, as well as many of the struggles in Puerto Rico, Mozambique, South Africa (or Azania as they accepted as its name), and Zimbabwe that existed between the late 70s and mid 80s. They too followed many of the same political beliefs as described here.

The quote from Cabral is true in one sense yet misleading in another, a fact which the blog proceeds (intentionally or not) to make pellucid, for it is the “ideas,” “the things in [peoples’] heads,” particularly in the form of values, principles, ideals, imaginings, what have you, that can and often do provide the necessary motivational impulse that skillfully combines the best of hearts and minds, that gives structure, shape and meaning to the struggle for “material benefits.” Hence, as Simone de Beauvoir reminds us, the lines often drawn between moral idealism and political realism are not as sharp and hard as often assumed or asserted. As Beauvoir wrote in one of her essays, the reflexive and thus reactionary response by conservatives to ideas and models of reform—let alone revolution—is that it is “impossible,” the antithesis of realism, utopian in the most pejorative sense, a response that, in the bosom of time, serves as self-fulfilling prophecy insofar as publicly and repeatedly “saying so” makes it so! Put differently, we do well to consider the wisdom enshrined in Beauvoir’s observation that “[g]aining an awareness is never a purely contemplative process; it is engagement, support or rejection” (note that this entails that it is partly a ‘contemplative process,’ that is, in the mind). This is why she can conclude that the “lucid political man who truly has a hold of things is also conscious of the power of freedom in him and in others.” To be sure, these ideas, be they “black nationalism,” “black consciousness,” radical praxis, liberation, freedom, egalitarianism, international and transnational solidarity, democracy, justice, human rights, individual and collective self-empowerment, power relations, structural transformation, alternative institutions, humaneness, socialism, what have you, do not emerge full-figured in the first instance, as it were, from the minds of the masses (‘the people’), a point well-made by Rudolf Barho in The Alternative in Eastern Europe (NLB, 1978):

“[I]n no known historical case did the first creative impulse in ideas and organization proceed from the masses; the trade unions do not anticipate any new civilization. The political workers’ movement was itself founded by declassed bourgeois intellectuals, which in no way means that the most active proletarian elements did not soon come to play a role of their own in the socialist parties and tend themselves to become intellectuals” [what, after Gramsci, we refer to as ‘organic intellectuals’].

Barho’s point may have been truer in the past than in our own time, but it does not detract from the significance of the refusal to draw a hard and fast distinction between the struggle to “win material benefits, to live better and in peace,” and the “fight for ideas.” We can further fill out this analogy between the “working class” in the history of the Left and black radical praxis. Thus, and by way of illustration, it is often the conservative, the condescending liberal, or the bourgeois class that unabashedly or arrogantly “strives to demonstrate the primitive and purely material character of the interests of the working class:”

“In the name of his spiritual authority, the bourgeois declares himself to be in a better position to define the conditions suitable for the working class than the working class itself. [….]

The standard of living that the worker demands is not required by his immediate needs, nor is it called for by dreams of compensation. It is the actualization, the expression of the idea that the worker has of himself, in the same sense that our body is the expression of our existence. It is the objective form that a transcendence takes on [existentialist jargon]. For this reason it is not absurd that a man is willing to risk his life in a strike, or in a war, in order to maintain or gain a certain standard of living. The aim of the striker is not so much an increase in salary, as a crude amount of money, but an increase of something he has gained; it affirms his power to improve his condition on his own.”

Thus, what on first examination appears to be simply and sufficiently characterized as “a fight[] to win material benefits, to live better and in peace,” may, in time be understood as something greater and grander than that, something inextricably and intimately bound up with something in the heads (and hearts) of not only intellectuals and revolutionary activists and leaders, but of the masses themselves: ideas, ideals, principles, values, and utopian imaginings (e.g., radical praxis, liberation, freedom, egalitarianism, international and transnational solidarity).

erratum: a fact which the blog post proceeds…

and please eliminate the second “something” in the last sentence (I know I should not comment when pressed for time but…)

Thanks for this insightful point. I could not agree more that all material struggles are also struggles for ideas. The value of Cabral’s admonition, I think, lies in the need for intellectuals and organizers to avoid the seductive notion that “the masses” are or SHOULD BE fighting JUST for the ideas in the heads of intellectuals or organizers. In other words, I see the quote in part as a call to recognize the dignity, wisdom, and legitimacy of the rank and file in any liberation struggle–to recognize and affirm their capacity for self-organization. To “return to the source,” as it were, by wholeheartedly committing one’s self to struggle alongside the oppressed in the name of their intimate and indigenous visions of liberation. Cabral’s quote reminds us that as intellectuals we must guard against the elitism that is embedded within our privileged social position. We have the luxury to theorize, but that does not mean that we have the right to speak for anyone or attempt to arrogantly impose our scheme of society on the masses. Rather, radical intellectuals must commit “class suicide”–they must disavow bankrupt privilege, pretense, and isolation by joining the mass struggle and helping to realize its material aims. The vibrant ideas of the subordinated masses can be fully realized only when their material realities have been transformed.

Very well said, thank you.