Interracial Intimacy in America: An Interview with Sheryll Cashin

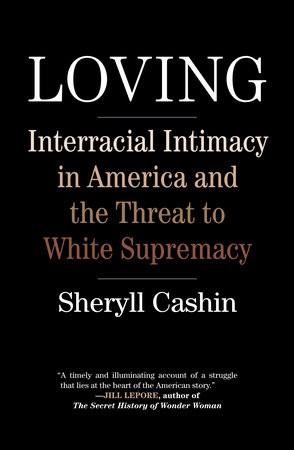

In today’s post, Melody Shaff, a student in Political Science at Boston University, interviews Sheryll D. Cashin about her new book Loving: Interracial Intimacy and the Threat to White Supremacy, which was released in June 2017 by Beacon Press. Sheryll Cashin writes about race relations and inequality in America. Her new book, Loving, explores the history and future of interracial intimacy, how white supremacy was constructed and how “culturally dexterous” allies may yet kill it. Her book, Place Not Race (Beacon, 2014) was nominated for an NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Non-Fiction in 2015. Her book, The Failures of Integration (PublicAffairs, 2004) was an Editors’ Choice in the New York Times Book Review. Cashin is also a two-time nominee for the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award for non-fiction (2005 and 2009). She has written commentaries for the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, Salon, The Root, and other media. Cashin is Professor of Law at Georgetown University where she teaches Constitutional Law, and Race and American Law among other subjects. She is Vice Chair of the board of the National Portrait Gallery, and an active member of the Poverty and Race Research Action Council. Cashin worked in the Clinton White House as an advisor on urban and economic policy, particularly concerning community development in inner-city neighborhoods. She was law clerk to U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. Cashin was born and raised in Huntsville, Alabama, where her parents were political activists. She currently resides in Washington, D.C., with her husband and two sons. Follow her on Twitter @SheryllCashin.

Melody Shaff: How did you come to this project? What are some of the experiences and factors that motivated you to write a book about interracial intimacy and the history of white supremacy in the United States?

Sheryll Cashin: I teach a course to law students called Race and American Law and Loving v. Virginia is one of the seminal cases we cover. I thought it offered a refreshing angle for considering why American race relations are so scarred and fraught. Most people do not realize that whiteness was constructed in this country mainly through the regulation of interracial sex and marriage. I was also intrigued by the sheer Strom-Thurmond-ness of a country once obsessed with bloodlines having such a long history of race-mixing. My own history reflects these ambiguities. I am a descendent of a white slave owner who had a common law marriage with a mixed-race woman of color. I am also the child of civil rights activists who subverted the old Jim Crow in part by recruiting white allies to march with them in the sit-in movement in Huntsville, Alabama.

My father, Dr. John L. Cashin, Jr., also founded a political party, the National Democratic Party of Alabama (NDPA), to give poor black sharecroppers newly enfranchised by the Voting Rights Act an alternative to the party of George Wallace. NDPA was born in 1967, the same year Loving v. Virginia was decided. Both were assaults on white supremacy. NDPA was backed by a biracial group of riotously humorous change agents. I inherited their sense of humor, irreverence, and impatience with supremacy and I brought that voice and perspective to writing Loving.

Shaff: The release of your new book coincided with the 50-year anniversary of the Supreme Court’s ruling in Loving v. Virginia. How would you summarize the historical significance and contemporary relevance of the case? In your view, how has Loving shaped interracial marriages—and more broadly, interracial intimacy—in the United States?

Cashin: The Loving decision struck down state bans on interracial marriage and said plainly that such laws had been “designed to maintain White Supremacy.” It was the first time the Supreme Court used those potent words to name what the Civil War and the resulting Fourteenth Amendment should have defeated. A dominant whiteness, constructed by law, was embedded in people’s habits. Chief Justice Warren wrote the unanimous opinion. Perhaps he thought that being transparent about this pervasive racial dogma would help cure the nation of its mental illness. While the case ended legal barriers, its true import is only beginning to be felt as social barriers have eroded. In 1958, when Richard and Mildred Loving married, only 4 percent of Americans approved of marriages between blacks and whites. Today 87 percent approve of interracial marriage.

I document five forms of rising interracial intimacy – marriage/cohabitation, dating, adoption, friendship, and virtual ties some audiences form with fictional characters or, say, a black President of the United States. I show how such intimacy is contributing to the rise of “cultural dexterity” a phrase I coined. It is the opposite of colorblindness, an enhanced capacity for being among and accepting people of a different race or culture, rather than demanding assimilation to one’s own culture.

Shaff: Tell us more about your research methods and methodologies? What kinds of primary sources did you use in the book? What did you find most interesting or surprising about the research you uncovered during the process of writing the book?

Cashin: This book, which begins in 1607 and ends with speculations about the future, does not purport to offer a comprehensive social or legal history. Instead it simply tries to tell a coherent story about what transpired with interracial intimacy over the centuries and what has, and has not changed, since Loving was decided. It is interdisciplinary. For the historical chapters I relied primarily on published texts by historians, or the writings and speeches of the people I feature in the book. In the chapter about the birth of white supremacy I relied heavily on Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on Virginia, for example. In the chapters about rising intimacy, I often cited the work of social scientists. I also interviewed some people about their interracial experiences and included their voices.

Most surprising to me was the economic origins of white supremacy. Whiteness was created to solve a class conflict between wealthy planters and poor white servants. It had political function and this dog-whistling to divide and conquer continues to this day.

Shaff: In Loving, we see a rather dramatic shift in lower class whites’ views on interracial relationships over time. Can you elaborate on this transformation? What do you see as the major factors that contributed to this shift and how has class dynamics shaped Americans’ views on interracial intimacy?

Cashin: In early colonial Virginia indentured whites and the bonded black and indigenous tended to be allies. They toiled alongside each other, fraternized, sometimes had sex, married, ran away or rebelled together. When the planter elite decided to transition from indentured servitude to black chattel slavery, they taught white laborers to distinguish themselves from blacks and others by elevating whiteness as a status with certain privileges. And they stripped black servants of rights they had enjoyed. Throughout American history, elites used supremacy to drive struggling whites away from multiracial alliances that might demand too much of the wealthy. Stoking loathing about race-mixing and fear about black men having sex with white women were key rhetorical tools for ensuring popular commitment to supremacy. This ideology, in turn, was the organizing plank for regimes of oppression that were essential to American capitalism and expansion – from slavery, to indigenous and Mexican conquest, to exclusion of Asian and other immigrants, to Jim Crow.

Shaff: In your book, you make a distinction between someone who is not racist and someone who is not culturally dexterous. Can you please elaborate on this point? Is there always a clear line between the two and why do you find this to be such an important differentiation?

Cashin: A person can be anti-racist but get little practice at robust pluralism. In other words, a dexterous person acquires the ability to enter a room and be outnumbered by people of another race by actually doing such things. And if one chooses to undertake the effort, the process of acquiring and honing dexterity is never-ending. For the culturally dexterous, race is more salient, not less. Those who have intimate relationships with people of another race can lose their blindness and gain something tragic, yet real – the ability to see racism clearly and to weep for a loved one and a country that suffers because of it.

According to a recent study, for example, a white person with a black friend predicts greater empathy and anger regarding how African Americans are treated, which in turn predicts greater support for and participation in collective action for racial justice. Because of the continued effectiveness of divide-and-conquer politics, union busting and gerrymandering, I don’t have much hope for a transformative class unity emerging in this country. The rise of culturally dexterous people who see and name racism, however, may be our only hope for disrupting tired race scripts. When a third or more whites have acquired dexterity, when they can accept the loss of centrality of whiteness and desire to join multiracial coalitions for what is right and fair, politics could return to being functional in America.

Shaff: What type of impact do you hope your work will have on the existing literature on Loving and interracial intimacy in the United States? What do you hope readers will take away from your book?

Cashin: A number of books and articles have been written on this subject. I believe my contribution is applying a much longer historical lens than is typical in this literature, and, perhaps foolishly, being willing to speculate in detail about the future. I hope readers will conclude that my optimism is not misplaced. In the final chapter I document the confluence of forces that transformed California politics, including rising intimacy, immigration, demographic change, the dying off of older generations more expectant of white dominance, and accelerating political engagement by racial minorities tired of being scapegoated by politicians. In two decades the Golden State went from majority-white, to gridlocked, to majority-minority to functional in its politics. Mean-spirited dog-whistling no longer works in that state. California has ended gerrymandering and is retreating from the war on drugs, leading on climate change, and investing more in education among other positive trends. In sum, I try to offer readers hope and encouragement to keep fighting for a beautiful America. I dare to imagine what the culturally dexterous class could dismantle and create, that is, what the third Reconstruction might look like.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Thank you for exploring the subject of white supremacy and interracial intimacy in writing…About time! We still have work to do here in Cali but from my travels, we may be further along to racial dexterity than some other states. My church is non-denominational and multiracial.