Cuba, Antiracism, and a New Revolution

January 1, 2017 was the first time since 1959 that Cuba has celebrated a New Year and the anniversary of the Cuban revolution without Fidel Castro. Sweeping into history in the 1950s, Castro, his 26th of July Movement (M26-7), and other members of the anti-Batista coalition drove U.S.-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista out of Cuba on December 31, 1958. Since then this time of year has held a special significance for the whole island, as national celebrations of Cuba’s liberation coincided with the beginning of a new calendar year. The festivities, some patriotic, others religious, some just really good parties, and lots including all of the above, fused the meta-narrative of Castro’s triumph over Batista with sentiments of new beginnings. Despite having made few public appearances since turning over leadership of the island to his brother Raul in 2008, the aging revolutionary leader’s death on November 25, 2016 makes this January 1 different.

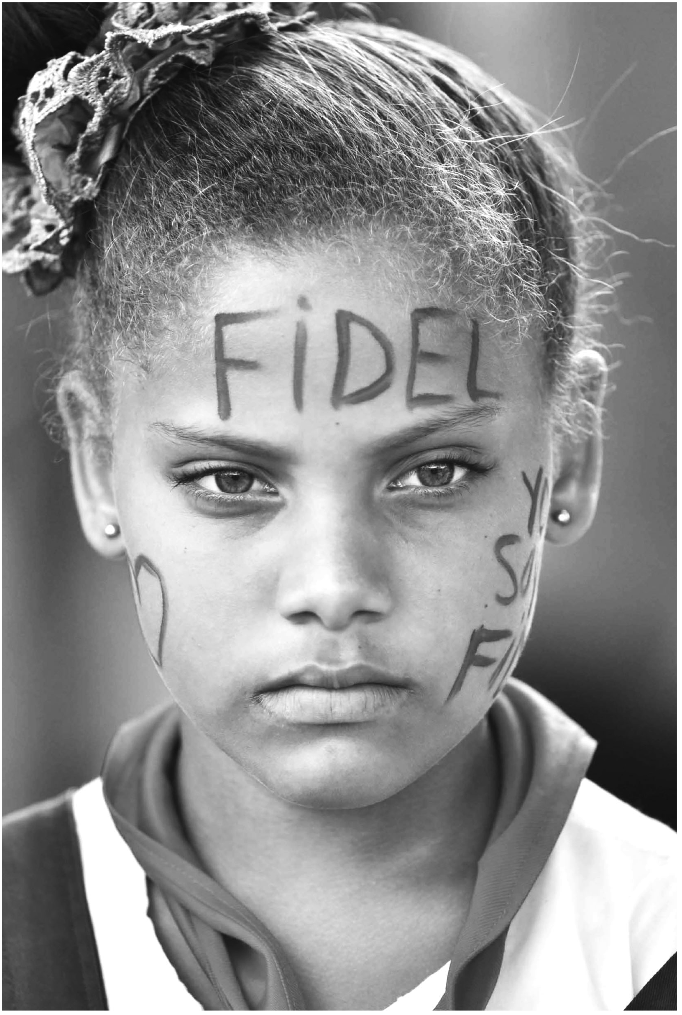

The new memorials to Fidel (signs, billboards, and photographs) now lining the streets of Cuba are one big change. While other revolutionary leaders (José Martí, Che Guevara, and Camilo Cienfuegos, to name a few) have always had a strong presence in Cuba’s revolutionary propaganda, images of Fidel Castro were absent before his death. Now the many photographs of Castro hanging in Havana’s Revolution Square and outside people’s windows give a new meaning to the images of Fidel riding victoriously into Santiago on January 1, 1959 published in Granma, the Cuban newspaper.

But similar to the polarizing reactions to Fidel’s death in November, the significance of 2017’s new beginnings for Cubans on and off the island is divided and will likely continue to marginalize people of African descent who make up between 30-60% of Cuba’s population.

After Castro’s death photographs of Cuban Americans of all ages celebrating in the streets in Miami contrasted with somber memorials in Havana and interviews with various world leaders describing the Cuban statesman as an inspirational icon. Many of the accolades came from people of African descent, including the second post-apartheid president of South Africa Thabo Mbeki, African American activist Bill Fletcher, Jr., and Afro-Cuban journalist Pedro Pérez Sarduy, whereas the images of celebrating Cuban Americans tended to show lighter-skinned or white Cubans dancing in the streets, waving Cuban flags, and urging “Fidel, tyrant, take your brother too!” While these diverging sentiments did not always divide evenly into global black support versus white exiles’ euphoria—there were many of all colors on either or both sides of this divide—the general polarization between those who saw Fidel as a champion of black and brown rights (Chicanos also applauded the revolutionary icon’s anti-imperialist stance) and those who saw him as an evil and corrupt dictator appeared to be racialized.

Using racism and antiracism as a mirror into the legacy of Fidel Castro explains these diverging attitudes. In the 1960s, the Cuban revolution identified racial discrimination as “one of the four battles” that Cuba had to fight, began integrating informally segregated schools and social clubs, and visibly supported African American civil rights struggles. In contrast, Cubans who arrived in South Florida in the 1960s were predominantly white upper-class urban professionals who claimed that racial discrimination could only be tackled after communism was defeated. In fact, this group distanced themselves from U.S. black demands for equal citizenship even as they received over $158 million in federal assistance from 1961–66 alone. Cuban exiles lost the global battle to be seen as antiracist to revolutionary leaders on the island by cloaking themselves in the language of democracy and freedom despite daily evidence of the lack of freedom and democracy available to African Americans in the U.S. south at the time. Rather, it was Fidel Castro and Cuban leaders, not Cuban exiles, who welcomed fugitive U.S. Black Panthers to the island, met with Malcolm X in Harlem, and repeatedly critiqued the “democrakkkia” (with three Ks in reference to the Ku Klux Klan) that they saw in the United States.

These diverging approaches to race and racism resurfaced when Castro died as people across the globe tried to make sense of the revolutionary leader’s legacy. Yet, in the midst of this uproar, the voices of Afro-Cubans remained mostly silenced, with a few notable exceptions, as others argued over how Castro approached blackness, racism, and colonialism. Many white Cuban exiles failed to see in the 1960s or today why Cubans of African descent might have supported the revolution. And even well-meaning global watchers often paid more attention to Cuba’s successes in the anti-colonial struggles in continental Africa than to the contradictory legacy of antiracism on the island.

As I’ve written before, the revolution’s approach to antiracism left much unfinished, especially as today’s deepening racial inequalities in the island’s emerging economy reveal how black and mulato Cubans have unequal access to capital from abroad and are often excluded from jobs in new joint business ventures that favor lighter skinned and white Cubans.

Surely the debates over Castro’s legacy will continue into the New Year, but while onlookers debate his legacy, some Cubans are living it and making it their own. Afro-Cuban activist Sandra Alvarez is one example. Alvarez is the author of the black feminist blog Negra Cubana tenía que ser (Black Cuban Woman I Had to Be). She celebrated her own anniversary, the 10-year anniversary of her blog, two weeks ago. In a post dated December 19, 2016, Alvarez describes the challenges and success of ten years of blogging about race, sexism, and homophobia in Cuba. She admits that it is difficult to blog about racism in Cuba, “a country [unlike the Unites States] where it is rare that a person will be murdered for being black.” Instead, she describes the prevalence of “racial profiling,” stereotyping, and racist jokes that target blacks in Cuba and says she wants her blog to draw attention to these attitudes despite the common misconception that racism doesn’t exist in socialist Cuba.

Most striking, Alvarez listed five goals of the antiracist movement in Cuba. I like to think of these as New Year’s Resolutions for Antiracism:

- A public politics of racial equality: Including making credit or financing available to people of African descent to open small businesses.

- Legislation that will specifically penalize racial discrimination.

- A larger number of people of African descent in positions of power and decision-making.

- Establish, from a center against racism, a tool that will serve as a common place to collect denouncements of racism.

- Reformulate the way race is collected on the census to gain a better understanding of the exact number of people of African descent in Cuba.

Maybe in 2017 instead of debating, celebrating, or memorializing the legacy of the Cuban revolution, we can get behind these ideas in Cuba and globally to work toward a revolution that lives up to its antiracist promises.

Devyn Spence Benson is an Assistant Professor of Africana and Latin American Studies at Davidson College and the author of Antiracism in Cuba: The Unfinished Revolution (UNC Press, 2016). Benson received her Ph.D. from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill in the field of Latin American History, where her research focused on racial politics during the first three years of the Cuban revolution. Follow her at Twitter @BensonDevyn.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Thank you for an informative post. I have one quibble: I don’t think we need view the processes of “debating, celebrating, or memorializing the legacy of the Cuban revolution” as crowding out consideration of and working towards achieving the five goals proposed by Alvarez, indeed, and for example, they could rightly be viewed as integral to any well-constructed debate of the legacy of Cuba’s “unfinished” revolution.

Gracias ~ Thank You for publishing this article of this world wide epidemic of racism that is not only a USA problem, but a Cuban problem as well. I applaud Ms. Alvarez in her leadership to promote the ongoing “Unfinished Revolution”