Conjuring the Black Radical Tradition

This is the fifth day of our roundtable on Cedric Robinson’s book, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. We began with introductory remarks by Paul Hébert on Monday, followed by remarks by Joshua Guild on Tuesday, Jennifer L. Morgan on Wednesday, and Carole Boyce Davies on Thursday. In this post, historian Austin McCoy documents the significance of disruptive protests and mass movements within the black radical tradition.

Austin McCoy is a Mellon Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow in Egalitarianism and the Metropolis at the University of Michigan. He recently completed his dissertation, analyzing the development of left-wing politics in the Midwest between 1967 and 1988. His research and teaching interests include African American history, political economy, labor, social movements and activism, and hip hop culture. Follow him on twitter @AustinMcCoy3.

Austin McCoy is a Mellon Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow in Egalitarianism and the Metropolis at the University of Michigan. He recently completed his dissertation, analyzing the development of left-wing politics in the Midwest between 1967 and 1988. His research and teaching interests include African American history, political economy, labor, social movements and activism, and hip hop culture. Follow him on twitter @AustinMcCoy3.

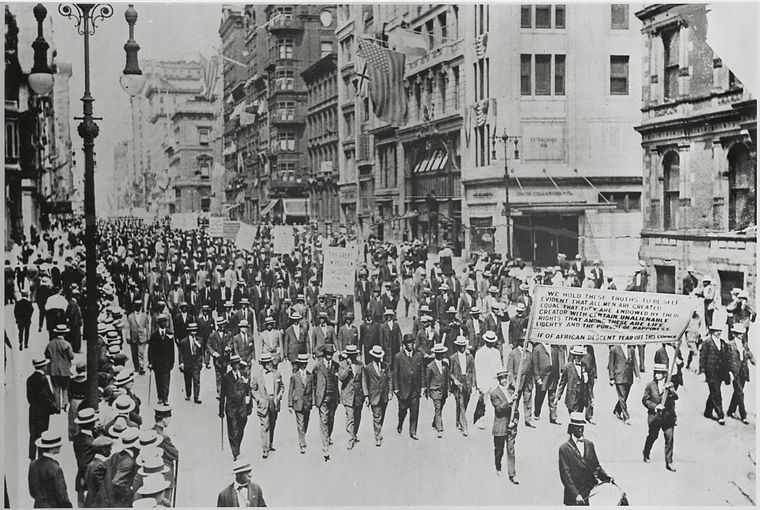

In response to police killings of black Americans and the deadly outcomes of decades of mass incarceration, hundreds, if not thousands, of black folks have engaged in various forms of disruptive protest. They have been blocking streets and freeways, interrupting public events, engaging in massive civil disobedience such as the Ferguson October protests and 2015 Black Friday action in Chicago, and even violently protesting in the streets of Ferguson and Baltimore. These protests, often under the Black Lives Matter (BLM) slogan, conjure what Cedric Robinson called the Black radical tradition.

In Black Marxism: the Making of the Black Radical Tradition, Robinson outlined how this tradition emerged out of the development of racial capitalism, centuries of collective black resistance to enslavement and imperialism, and black leftist intervention into Marxist theory. While political pundits often pay attention to the policy outcomes of the movement, Robinson reminded us that transforming policing and eradicating the system of mass incarceration requires massive disruption with radical political goals.

I use the word “conjure” deliberately because the American system of representative democracy and federalism, especially in the contemporary two-party form, has tried to suppress the Black radical tradition as well as other forms of radicalism on the left. There is a long history of criminalizing black protest stretching back to enslavement. New York and New Jersey, along with other states, passed slave codes to prevent uprisings. After the Compromise of 1877, white southerners waged a violent counterrevolution against black freedom after the Civil War and Radical Reconstruction. National, state, and local law enforcement institutions responded to the 1960s urban rebellions and the surge in radical politics with the militarization of policing. Americans also consent to the military and police having a monopoly on the use of collective violence. Law enforcement’s control over the use of violence has proven costly —as shown by the hundreds of black Americans killed by the police.

Additionally, many Americans–white and black, conservative and liberal–rely on rhetorical and discursive strategies to discredit certain forms of black politics, especially disruptive protest. The myth of nonviolent social change is a crucial pillar of American exceptionalism. We celebrate the nonviolent transfer of power anytime we elect a new president. Dead black radicals are incorporated into this myth. Many critics of disruptive protest often invoke a conservative image of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to discipline activists and validate myths of nonviolent social change.

There are at least two important outcomes when black radicals utilize disruptive protests. The first is to disrupt normal operations and to create a crisis in governance. The production of crisis by those conjuring the radical tradition, and sometimes in concert with external events such as war and economic depression, creates the possibility for delegitimizing political and economic institutions, dominant ruling ideologies, and oppressive social relations. If mass disruption is successful, then it can create the space for radical or revolutionary change. For many black radicals such as W.E.B. Du Bois and Angela Davis, Reconstruction represented such a period where the country had to expand the boundaries of freedom and citizenship, allow for the development of black political power, build new institutional structures such as public education, and consider how free black labor would affect the U.S. economy.

The second goal for many black radicals is to emphasize the multiplicity of tactics and strategies needed to overturn racial orders in order to achieve liberation. Thus, black radicals in the United States did not limit themselves to the traditional paths within a representative democracy as the only pathway towards radical social, economic, and political change. Disruptive protest has always been key. Black Americans escalated the use of sit-ins to disrupt businesses, reveal the violence needed to maintain racial segregation, and galvanize black activists across the country.

Recently, activist-journalist Shaun King conjured the Black radical tradition when he called for the escalation of tactics. Taking his cues from the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Montgomery Improvement Association, King advocates for the use of economic pressure. “For the past two years, we’ve protested all over the country, and my gut reaction used to be that it hadn’t accomplished as much as it should have – that the energy required for those protests didn’t meet the meager reforms that we’ve achieved. […] It is time, brothers and sisters, for us to make a unified national pivot. Our protests, of course, must continue, but we must add a critical new layer on top of them. It is time that we organize a passionate, committed, economic boycott,” King wrote. After soliciting reader feedback, King has since articulated an extremely detailed organizing plan that suggests a long-term disruptive effort.

In his call for a massive boycott, Shaun King acknowledged that critics would try to use a sanitized image of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to halt the escalation. Shaun King pushed back—he pointed to Dr. Martin Luther King’s desires to escalate civil rights protest though the Poor People’s Movement. Looking for alternatives to urban rebellion—and seeing prior expressions of nonviolent direct action as ineffective in addressing poverty and stopping the Vietnam War—Dr. King called for massive civil disobedience. “Mass civil disobedience as a new stage of struggle can trasmute the deep rage of the ghetto into a constructive and creative force. To dislocate the functioning of a city without destroying it can be more effective than a riot because it can be longer-lasting, costly to the larger society, but not wantonly destructive,” King declared.

Dr. King understood that massive disruptions could produce revolutionary moments where radical change becomes possible. King surmised, if poor Americans could get Congress to pass legislation to ensure a guaranteed income, then that would represent a positive step forward in the fight against poverty. If Congress could not, however, then the movement would create such an intolerable political situation that it would throw the political and economic system into question.

Coda—Connecting Mass Disruption and Prison Abolition

Organizing a massive boycott would represent an incredible feat, and could force many Americans to reckon with racist and violent policing. Yet, it is important to connect mass disruption with radical goals. It is also important to link various forms of massive disruption because there is a greater chance of creating the type of structural crisis needed to achieve radical goals if pressure comes from various sources.

Shaun King would do well to draw from Angela Y. Davis, another key figure in the Black radical tradition, and connect his call for a national boycott to prison abolition. Prison abolition—and the concomitant dismantling of racist policing and the public- and private-sector institutions undergirding the system—would force many to rethink the criminalization and disposability of people of color, particularly black Americans.1 It would also create a labor and economic crisis as the closing of prisons would throw millions of Americans—prisoners and workers within the system of mass incarceration—back into an already constrained labor pool. Prison abolition, or, really, the dismantling of the whole system of correctional facilities, may leave Americans with a question similar to the one that the United States faced when dealing with deindustrialization and the restructuring of the U.S.’s industrial economy that started during the 1950s: What to do with surplus labor? Obviously, the system of mass incarceration that began to take shape during the early-1970s helped absorb the labor surplus. But, the killing of black Americans by that system has thrown it back into crisis.

King’s call for a massive national boycott could be broadened to incorporate the current weeks-long national prison strike. The connection is rather obvious—racist policing is connected to the system of mass incarceration that has emerged in the growth in the last several decades. But massive disruption should not rest upon one strategy or tactic. Strikes inside prisons, as well as in plants and other workplaces, would apply even greater pressure on the U.S. economic and political system. Even though it is a longshot—all revolutions and radical breaks in society are uncertain—the combination of boycotts, work stoppages, and the paralyzing of cities could force a reckoning, or as Davis, Reverend William Barber, II, and Keeanga-Yahmatta Taylor, have mentioned or advocated for—a third Reconstruction.

- BLM co-founder Patrisse Cullors admitted that the movement as a whole has failed to center (police) abolition in its public discourse. While Cullor acknowledges that achieving police reforms are important, she believes in abolition. See Christina Heatherton, “#BlackLivesMatter and Global Visions of Abolition: An Interview with Patrisse Cullors,” in Policing the Planet: Why the Policing Crisis Led to Black Lives Matter, eds. Jordan T. Camp and Christina Heatherton (New York: Verso, 2016), 36. ↩

Very timely and relevant essay. Thank you for it.

Can you say more about how you’re defining conjure? The language of conjure seems to be interlaced with your discussion of suppression, but I’m not sure how your “deliberate” use of the term should be understood to work in this instance…I think I know what you mean, but I would especially like you to say more about it. More specifically, I’m interested in how you’re deliberate use of conjure suggests the ways or process for accessing it…does the fact of suppression carry its trace?

Thanks again for sharing such thoughtful work.

Austin —

I love the “conjuring” concept — are you connecting it at all to something beyond the criminalization/delegitimization of Black protest? I’m thinking of Robinson’s idea that the Black radical tradition is to a certain degree unknowable to Western epistemology; it can’t really “see” Black radicalism on its own terms. To me, “conjuring” evokes the idea of bringing into being something that is otherwise impossible to grasp…..

I too am intrigued by your use of conjuring and for me evokes the challenge to re-imagine past BRT practices in such a way that one sets in motion something pragmatic in the here and now. Is this a possible interpretation ?