Black Women Hustling off The Grid: An Author’s Response

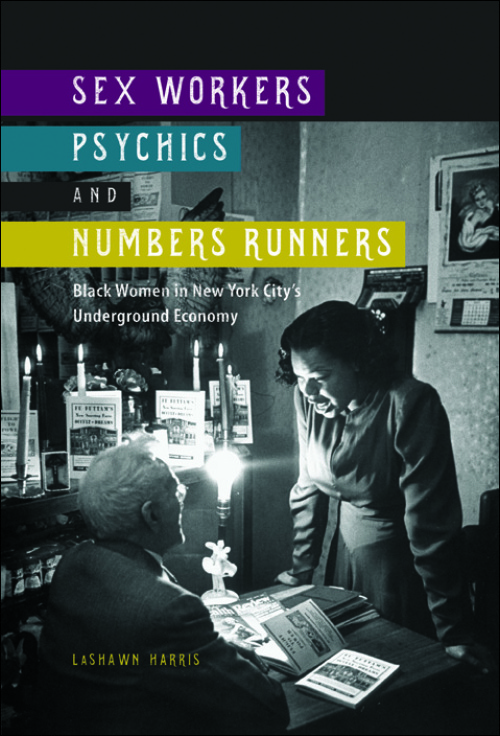

Today is the final day of our roundtable on LaShawn Harris’s new book, Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners: Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy (University of Illinois Press, 2016). On Monday, blogger Keisha N. Blain introduced the book and its author followed by remarks by Julie Gallagher on Tuesday; Shannon King on Wednesday; Talitha LeFlouria on Thursday; and Brian Purnell on Friday. In today’s post, Professor Harris offers a response.

Dr. Harris is an Assistant Professor of History at Michigan State University. Completing her doctoral work at Howard University in 2007, her area of study focuses on twentieth century United States History. Harris has recently published articles in the Journal of African American History, Journal for the Study of Radicalism, and the Journal of Social History. Her first book, Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners, examines the public and private lives of an all-too-often unacknowledged group of African American female working-class laborers in New York City during the first half of the twentieth century.

Car-jackers in Newark, New Jersey, Lean Drink manufacturers in the American South, gun runners in New York City, and abalone poachers in South Africa; These are just a few of the global underground entrepreneurs profiled on cable television show Black Market. A riveting thirty-minute reality documentary series, Black Market is hosted by African American actor Michael K. Williams. No stranger to studying illicit markets, Williams portrayed Baltimore gay stickup man Omar Little on HBO’s groundbreaking series The Wire and played 1920s Atlantic City bootlegger Chalky White on HBO’s Boardwalk Empire. Premiering in July 2016, William’s Black Market investigates multi-billion dollar global underground enterprises, illuminating the varying socioeconomic factors motivating individual participation in off-the-books labor.1 Episodes demonstrates how less privileged people confront a sluggish 21st century world economy and unemployment market, and captures the hidden stories and voices of individuals who hustled off the grid. Yet, women’s narratives are grossly missing from the series. Black Market imagines global underground markets as spaces that afford men economic and entrepreneurial opportunities.

Like the show Black Market, women in general and black women in particular are absent from historians’ intriguing studies on employment that sidestepped government regulations and city and state statutes. Until recently, historical scholarship on early twentieth century American urban underground labor markets depicts a world controlled by men from various racial and ethnic and class backgrounds. Moreover, within our historical imagination, but certainly not within archival records, informal labor sectors are routinely interpreted as spaces where men labored, socialized, and articulated ideas about the urban landscape, politics and gender roles, and masculinity. At the same time, if women do appear in the scholarship, they are often depicted as powerless and passive, as subordinate sidekicks to male protagonists, and as secondary actors within a larger narrative that centers how men used nascent underground markets to tackle joblessness, underemployment, and racial exclusion.

Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners contests the view that New York City’s burgeoning informal labor markets were masculine spaces, suggesting that early twentieth century women of African descent established themselves as informal economy wage laborers and entrepreneurs. It argues that the city’s underground economy served as a catalyst in working-class black women’s creation of employment opportunities, occupational identities, and survival strategies that provided financial stability and a sense of labor autonomy and mobility. Before I even considered writing a book about urban informal laborers, I knew from first-hand experience that women participated in New York’s informal labor sector.

Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners contests the view that New York City’s burgeoning informal labor markets were masculine spaces, suggesting that early twentieth century women of African descent established themselves as informal economy wage laborers and entrepreneurs. It argues that the city’s underground economy served as a catalyst in working-class black women’s creation of employment opportunities, occupational identities, and survival strategies that provided financial stability and a sense of labor autonomy and mobility. Before I even considered writing a book about urban informal laborers, I knew from first-hand experience that women participated in New York’s informal labor sector.

Growing up in New York City during the 1980s and 1990s, I encountered and observed these imaginative laborers on a daily basis. Non-licensed Harlem hair-braiders corn-rolled my hair for a reasonable price, low-level narcotics dealers sold drugs in my neighborhood, and street & subway boosters sold me counterfeit designer bags and bootleg movies on Bronx streets. Motivated in part by these memories and experiences, my intention, in researching and writing the book, was to produce a study that broadened conversations about women’s work while filling gaps within black women’s labor historiography. My objective was to transcend historical scholarship that focused on domestic and industrial work, and to probe into how unreported employment benefited poverty-stricken women. This line of research shifted as I located underutilized archival collections at the New York Municipal Archives and New York City Public Library. Raising new questions about New York black women, I investigated factors stimulating women’s labor choices and their pursuit of financial success, occupation autonomy, and urban pleasures. At the same time, I was also interested in investigating the rewards and risks associated with unreported employment. Despite the difficulties of conducting research on individuals who embraced a culture of dissemblance, I was fortunate to locate primary sources that uncovered some women’s horrendous and unsuccessful labor experiences as prostitutes, fortunetellers, and con artists.2

Reviewers’ responses and critiques of the book were thought provoking. Their comments raised questions about policing and criminalization, community resistance, research methodology, and informal labor sectors outside a northern context. Talitha LeFlouria, whose recently published monograph underscores the difficulties of researching women whose lives were confined by crime and legal confinement and race and gender exclusion, indirectly probes questions about the future of black women’s labor histories. LeFlouria rightfully observes that future exploration on women’s labor will focus more on urban southern women’s unreported home-based endeavors as beauticians, seamstresses, and food vendors. LeFlouria makes a great point, reminding me of Tera Hunter’s important 1997 study on post-Civil War southern black women. Hunter contends that Atlanta, Georgia women entered urban informal economies, taking in boarders, establishing alcohol and sex businesses in their homes, and travelling on busy thoroughfares with their food carts. No doubt, this subject warrants further research. Because of limited or unavailable primary sources as well as scholars’ preoccupations (myself included) with illicit economies, including sex trafficking, gambling, and drug and alcohol selling, less attention is paid to informal labor that was legal but unlicensed.

Shannon King makes several salient points. King, whose 2015 book on pre-WWII Harlem addresses police brutality, labor and housing activism, armed self-defense, urban leisure, and community formation, focuses on my discussion on Harlem’s numbers racket and numbers Queen Madame Stephanie St. Clair. King is chiefly concerned with the interracial and ethnic rivalry over the city’s profitable gambling racket. King “wonders if the black community’s response to [white crime figures like] Dutch Schultz was not only an anti-crime position but also a defense of black autonomy expressed through black-nationalism or “self-help” economic.” Blacks’ contestation over white numbers bankers’ efforts to control Harlem’s policy racket took many forms, including verbal threats and physical violence. King is correct in suggesting that resistance against white racketeers goes beyond blacks’ efforts to combat neighborhood vice. My analysis on the numbers racket could have explored this point a bit more. Black New Yorkers’ varying responses to white numbers bankers was about defending and protecting community autonomy and black self-help economies, and a bold statement about who should control what they perceived as a black economic pastime. Some blacks reasoned that white control over the numbers game was an extension of racial exclusion and white supremacy and an attempt to limit and undercut black entrepreneurship and economic mobility.

Julie Gallagher and Shannon King rightfully highlights that Madame Stephanie St. Clair was a unique individual. The Caribbean immigrant successfully dominated New York’s male-controlled gambling racket, she violently assaulted her two-timing second husband, and she craved public attention. Conversely, the Numbers Queen “was a fierce race advocate who defied every convention,” challenging white patriarchy and police violence and similar to many 1920s Harlem activists exposed municipal leaders’ unethical ties to organized crime. Recognizing St. Clair’s community advocacy, King questions if the Policy Queen, given her “community activism, self-determination, economic nationalism,” and entrepreneurial spirit, is a “New Negro.” I have reservations about identifying St. Clair as a “New Negro.” Like many New Negro activists, St. Clair regarded “the police as the coercive arm of the state, which neither protected blacks nor necessarily represented justice in black communities across the nation, [and] “challenged the Old Negroes, bringing to the fore, or airing the thoughts that many blacks expressed in the saloons, on the streets, and in their homes.”3 As articulated in her newspapers writings, St. Clair was a strong proponent of race, gender, and class equality, racial uplift, political enfranchisement, and economic empowerment. Her commitment to racial advancement was buttressed by personal struggles with urban inequities and intense police surveillance. So yes, St. Clair at one level could be considered a New Negro. On the other hand, St. Clair, at times, did not neatly fit into the New Negro category or New Negro activists’ ideas about respectability politics. Understanding the limits of race and gender exclusion and mastering the art of hustling, St. Clair was self-centered and ambitious, she injected herself into the media when it benefited her, and she manipulated her identity politics when she saw fit. Because of prescribed gender constraints and a personal desire for economic wealth she exploited messages of racial and community uplift to her advantage. For me, St. Clair’s public promotion of community advancement as well as her desire for wealth and notoriety often blurred, making it difficult for me to explicitly identify her as a New Negro.

For Brian Purnell and Julie Gallagher, Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners uncovers the “inherently complicated and diverse” lives of women, giving “voice to the humanity buried in anti-vice reports and sensationalist headlines.” It “does not tell a one-size-fits all story of black women making a living off-the-books” and “refuses to turn sinners into saints, or to traffic in one-dimensional depictions.” Revealing women’s multi-layered laboring activities, economic pursuits, and private lives was done intentionally. The book refutes assumptions that all informal laborers were financially strapped, that all were admired by neighborhood folks, and that all attained economic prosperity. Underground laborers experienced varying levels of success and they entered informal markets in different ways. Indeed, many working-poor women viewed unreported labor as possible avenues toward affording high city costs and confronting labor discrimination and the 1930s economic downturn. Others reasoned that informal labor offered opportunities to construct new labor identities, escape unskilled labor and family dysfunction, and secure wealth, sexual pleasures, and employment mobility.

Moreover, New York City’s rapidly changing socioeconomic, cultural, and political landscape of the 1920s & 1930s, including black urbanization and white immigration, and the emergence of criminal syndicates, shaped black women’s labor selections. Thus, wealthy Harlem street vendor Lillian “Pig Foot Mary” Harris Dean, scheming con artist and murder victim Cecelia Sargent, and other women’s entry into New York City’s parallel economy were not monolithic.4

The last issue I’ll address concerns my methodology. Brian Purnell asks: “How can a researcher and writer find information and recreate a story about people and practices that, by their very nature, did not want to be found or known?” As I stated in the book, the process of researching city women’s unreported labor was no easy task. For this project, I combed through multiple primary documents, including birth and death certificate records, newspapers, race reform and charitable organizational records, anti-vice investigation reports, immigration and naturalization papers, and city and state court and prison records. These materials provided a window into the hidden and versatile lives of New York black women. When read together and against each other, these sources filled gaps about the experiences of underground laborers and addressed questions that could not be answered by utilizing traditional manuscript collections. Yet, available primary sources also limited efforts to uncover broad representations of New York’s informal economy and its’ participants. Piecing together extant documentation left me with disjointed and conflicting narratives and raised a new set of historical inquiries that could not be addressed in the study. Research gaps and unavailable primary materials pushed me to situate my subjects within secondary scholarship and gender studies frameworks and to critically dissect the documents I did have access to.

I am thankful for Talitha LeFlouria’s Julie Gallagher’s, Shannon King’s, and Brian Purnell’s participation in the roundtable. Special thank you to moderator Keisha Blain and the African American Intellectual History Society (AAIHS) for selecting Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners for review. Reviewers offered constructive criticism and sparked rich dialogue about my work. I am pleased that commentators consider the book to be a contribution to African American women’s labor historiography. I hope the book continues to stimulate more conversations about the diverse ways urban black women lived and labored. I hope this study opens up new avenues of research on African American women.

- Black Market is on cable network Viceland. “The Wire’s Michael K. Williams Goes Face-to-Face With Real World Criminals on Black Market,” esquire.com http://www.esquire.com/entertainment/tv/news/a45905/black-market-michael-k-williams-trailer/ (accessed August 1, 2016). ↩

- Darlene Clark Hine, Hine Sight: Black Women and The Reconstruction of American History (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), 37. ↩

- Shannon King, Whose Harlem Is This, Anyway?: Community Politics and Grassroots Activism during the New Negro Era (New York: New York University Press, 2015), 169, 173; Erin Chapman, Prove It On Me: New Negroes, Sex, and Popular Culture in the 1920s (New York: Oxford University, 2012). ↩

- “Mrs. John Dean, Colorful Character, Buried Here Following Death in West,” New York Amsterdam News, July 24, 1929; “Mrs. L. H. Dean Leaves on Sox Months Tour to Far-Off Pacific Coast,” The New York Age, August 18, 1923, 8; Marvel Cooke, “Woman of Affair,” New York Amsterdam News, January 20, 1940, 15; T.R. Poston, “Murder Will Out? Who Was the Strangler of Vivacious Cecelia Sargeant? Young Lady of Many Affairs,” New York Amsterdam News, January 17, 1934, 9; Fifteen Census of the United States, 1930. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1930; Cecelia Sargent Death Certificate # 15942, Department of Health of The City of New York Bureau of Records, New York Municipal Archives. ↩

Excellent!!! I look forward to reading what you will produce in the future. Thanks again for your pioneering work!

This would make a great movie! Enjoyed this roundtable.

Excellent response, Prof. Harris! I wonder if they’re is necessarily a conceptual conflict between New Negroes and outlaw, like St. Clair folks? I might add that I also thought your methodology section, particularly the ways that you spoke to how the authors and production of the documents were contested, was significant. I think your methodology section powerfully bespeaks to how the production of archives are always and already filtered with gendered, raced, and class dynamics, complicating both the reading of the sources as well as how we, as historians with our own biases, the presentation of the voices of the subaltern.

Excellent! Looking forward to teaching this in my African American History Since Reconstruction course. It will follow readings on black women’s club movement.

Thank you, Dr. Harris, scholars, and AAIHS for this great roundtable.

Dr. Harris–your book is inspiring, and your methods are instructive. What an amazing story–yes make the film!