As Proud of Our Gayness As We Are of Our Blackness

Today’s guest blog post is written by Jonathan Bailey. A native of central Virginia, Jonathan currently resides in Baltimore, Maryland where he is a third year doctoral student at Morgan State University studying African American History. His research centers on black sexuality, civil rights, and urbanization in post-Civil Rights America. His dissertation focuses on African American LGBTQ political activism in the Baltimore-Washington, D.C. metro area.

Today’s guest blog post is written by Jonathan Bailey. A native of central Virginia, Jonathan currently resides in Baltimore, Maryland where he is a third year doctoral student at Morgan State University studying African American History. His research centers on black sexuality, civil rights, and urbanization in post-Civil Rights America. His dissertation focuses on African American LGBTQ political activism in the Baltimore-Washington, D.C. metro area.

***

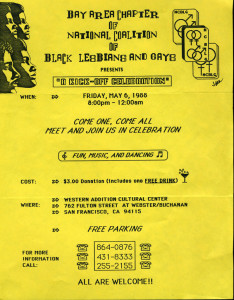

In the spring of 1984, the National Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays (NCBLG) called upon their fellow sisters and brothers of African descent to join them in black pride and solidarity to build a movement where issues surrounding blackness and sexual identity were at the core.

The NCBLG was one of a number of growing black queer national organizations that fought to end the increasing racist attacks against the black community and other people of color. They also condemned the increasing right wing attacks against the lesbian and gay community. Furthermore, they condemned the refusal of the Reagan administration to provide adequate funding for AIDS and other health crises. Indeed, the formation of countless black queer organizations during the 1980s and 90s underlines the crux of this blog post and my broader research on the social and political development of black queer identity in the United States.

Beginning in the late 1970s, a growing number of black queer activists created political and educational organizations that provided support and advocacy for individuals and organizations on issues affecting the black lesbian and gay community. For example, Renee McCoy, NCBLG’s former Executive Director recounted the importance of black queer organizations and said, “Well, the truth of the matter is that we have not overcome at all. Racism still limits our access to quality living. Homophobia and sexism continue to restrict our social interactions and dissolve the very fiber of our communities.”[1] As such, the birth of organizations such as the NCBLG signified that there was much work to be done to eliminate racism, homophobia, and poverty in society. McCoy’s statement relates to the very essence of why black gays and lesbians understood the necessity of forming all-black LGBTQ groups.

It was easier for the black community to oppose gay rights and express homophobia, and also for the gay community to acknowledge their own racism without recognizing how it affected the LGBTQ African American community. Rendered invisible in both black and gay spaces, black queer activists worked diligently to create safe sociopolitical outlets for black lesbians and black gay men. Furthermore, they fought to attain political power and recognition in non-partisan, non-violent, but aggressive ways for the survival, growth, and acceptance of themselves as gays and lesbians. Their struggle for human and civil rights was not just limited to black gay men and lesbians, but also to women, youth, physically challenged, senior citizens, prisoners, Native Americans, Asians, and Latinos/as.

Between the years of 1978 and 1996, the African-American LGBTQ community began to showcase their own identity that acknowledged both their race and sexuality. Alongside this development, a number of activists, artists, students, and organizations produced written, oral, and visual documentation that represented the ascension of the African-American LGBTQ community. (examples below)

Black LGBTQ activists held a conference for Third World Gays and Lesbians in Washington, DC up until 2003 when the National Black Justice Coalition (NBJC) was founded. To date, NBJC remains the only civil rights organization dedicated to empowering black lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered people.

Studies on LGBTQ populations in the United States often highlight gay and lesbian populations in larger metropolitan areas such as New York City, San Francisco, and Chicago. But when gay and lesbian history began to emerge within the academy, not only class divisions but racial divisions within the larger LGBTQ community were overlooked. Studies tended to focus more on how gays and lesbians developed a social-political identity that led to a separate and distinct minority in the United States. Further still, recent work on the topic focuses more on small towns and disparate regions in the country, and on racial and gender issues.[2] From my research, I have not found a thorough analysis of the formation of the African American LGBTQ community in any of these areas.

The African-American Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgendered community in the Baltimore and Washington, D.C metro area formulated a distinct LGBTQ community through building and sustaining their own social spaces and by advocating for causes that were unique to their communities through political activism. Washington D.C. and Baltimore were home to a number of black LGBTQ institutions that spurred a national black queer identity. Starting in the late 1970s, the black gay community built their own social, political, and cultural spaces. Despite Baltimore and DC being a largely black-led city, they still suffered from overt racism. When gay black writer Gideon Ferebee, Jr. moved to DC in the mid-1970s, he recounted the racism he experienced in mostly gay spaces. “The racism was very overt,” he remembers. Continuing he says, “in terms of you’d go to bars, and you’d have two or three picture IDs [if you were black] and there were dress codes.”[3] Racial incidents that were experienced by Ferebee encouraged the development of black gay social clubs such as the Clubhouse in Washington, DC, which became one of the primary social spaces for LGBTQ African Americans.[4]. In Baltimore alone, there were over ten lesbian and gay bars that specifically catered to black lesbians and gay men.

In addition to forming their own black social spaces, racism also served as a catalyst for black gay political organizing. Many LGBTQ African Americans felt that their needs were not recognized by most LGBTQ organizations. As such, a number of these activists rallied everyone they knew by placing ads in Washington and Baltimore’s LGBTQ newspapers to see if other African Americans had any interest in an organization that would focus on political issues, social change, homophobia in the black community and racism in the white community.[5] In 1978, Billy Jones Hennin, of Washington DC, with Louis Hughes, a black gay male activist from Baltimore, formed the D.C. and Baltimore Coalition of Black Gays, the country’s first long-standing black LGBTQ political organization.[6]

In addition to their social and political development, black gay artists ushered in a cultural movement that furthered the visibility black LGBTQ individuals. The burgeoning black LGBTQ performance scene in the early and mid-1980s flourished. A collective of gay black male and lesbian poets, performers and writers created work that spoke to the daily experience of the black gay community.

Black lesbians and black gay men signified a social and political presence in America that actively combated homophobia and sexism. Although African Americans made significant strides politically, socially, and economically since the Civil Rights Movement, and gay rights were becoming a legitimate issue in the country by the 1980s, black lesbians and gays realized that they faced serious and complex challenges that were unique to them. As such, a growing number of black queers grew weary of having their existence circumscribed to the privacy of their own rooms where no one can see them – splitting themselves into separate compartments maintaining a façade of “straightness” where caresses and love are forbidden.

The undiscovered history of the movement for black lesbian and gay solidarity highlights how social movements in the United States can be dictated by race, gender, class, or sexuality. Ultimately, Black gay men and lesbians were determined to tackle some of the major issues that affected both their race and sexuality. They were as proud of their gayness as they were of their blackness.

[1] Renee McCoy, “The Truth of the Matter,” Black/Out: The Magazine of the National Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays. Vol.1, ¾, 1987, 3.

[2] Ferguson, Roderick, Aberrations in Black: Toward A Queer of Color Critique (University of Minnesota Press, 2003). Hanhardt, Christina, Safe Space: Gay Neighborhood History and the Politics of Violence. (Duke University Press, 2013). Holmes, Kwame, Chocolate to Rainbow City: The Dialectics of Black and Gay Community Formation in Postwar Washington, D.C., 1945-1978. (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Doctoral Dissertation, 2011).

[3] Beemyn, Genny. Queer Capital: A History of Gay Life in Washington, D.C. (Routledge: New York, 2014), 205.

[4] At it’s height in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Clubhouse would attract between eight hundred and thousand people on an average Saturday night.

[5] Interview with Billy Jones-Hennin, March 2013.

[6] Jones-Hennin Interview.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.